Michael McGuire

Investigation of the rhetorical dimensions of music and song is still in its infancy. The few studies that have been conducted to date focus primarily on social protest music; songs that are blatantly didactic in purpose, method, and content. Consequently, artists perceived primarily as musicians rather than musical orators have received less attention than might otherwise be warranted. One such artist is Bruce Springsteen.

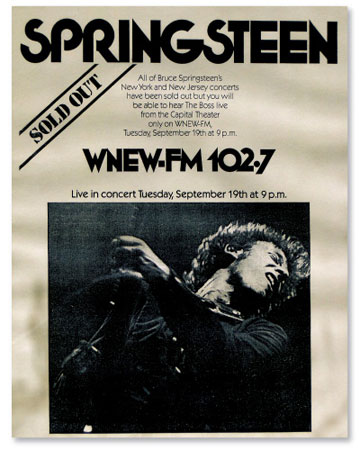

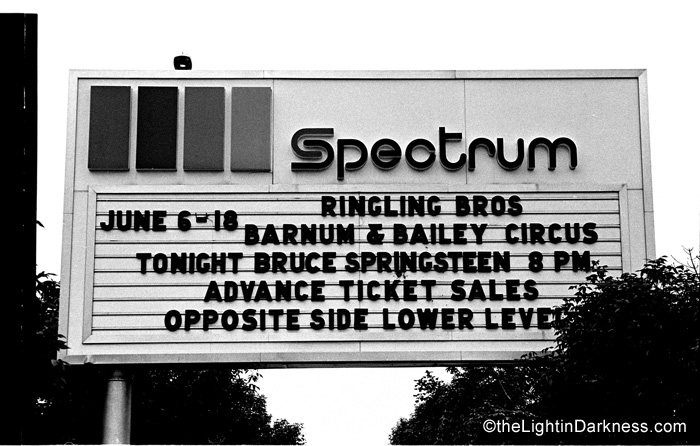

During the week of October 27, 1975, Springsteen appeared on the covers of both Time and Newsweek where, among other accolades, he was proclaimed the new Bob Dylan. That same year Jon Landau, music editor of Rolling Stone, wrote: “I have seen the future of rock ‘n roll, and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” Over a decade later, Springsteen remains a rock phenomenon. His concerts are sellouts and his album sales run into the hundreds of thousands. He is on the verge of becoming a cultural myth as well as a rock legend. References to “the Boss” punctuate primetime television, and an educational album featuring “Bruce Stringbean” has been produced by Jim Henson and the Muppets.

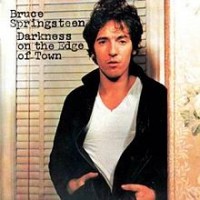

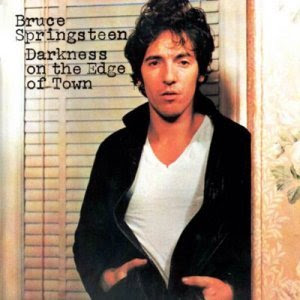

In this essay I offer a rhetorical analysis of the three themes that bind together most of Springsteen’s music: despair, optimism, and responsibility. To understand Springsteen’s message is not only to recognize these central themes, but to appreciate the complex, dialectical relationships between and among them. We will focus on three of Springsteen’s most popular albums: Born to Run (1975), Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), and The River (1980). Realizing that lyrics cannot be criticized *in vacuo* as if they were poetry independent of important musical accompaniment, we will observe relationships between the words and music. However, our purpose is to uncover the synthesis Springsteen structures among his three major themes of despair, optimism, and responsibility by observing first the nature of each theme and then their interrelationships.

A few words about our method of inquiry are in order at the outset. We will not focus on the chronological growth of Springsteen as an artist or the sequential development of his music, as if we saw it reaching toward some goal or endpoint. Such discussions could prove interesting and valuable, and popular authors have been providing them to demonstrate Springsteen’s development, especially as a composer and producer. But with contemporary rock music we confront an art form especially suited to non sequential analysis. The average rock album contains from eight to twelve songs, and even when we consider what has come to he called a “concept album,” there is not usually a necessary sequence of songs.( The “concept” generally is one of instrumental or lyrical unity which does not require serial or diachronic presentation to he grasped. To grasp the thematic unity of a single rock album often requires a restructuring of its units; the same observation applies to an attempt to isolate themes that recur in a number of albums.

This sort of structuralist approach to rhetorical criticism has been both advocated and illustrated. In The Philosophy of Literary Form, Kenneth Burke discusses finding “associational clusters” in artistic works and a process for examining such clusters to disclose “what goes with what.” The disclosure of clusters usually involves some deconstruction and reconstruction of an author’s works to put together the parts of the clusters which fit thematically but not narratively. A similar process of reconstruction is the heart of structuralist criticism which seeks out thematic units and the relationships among them.

This sort of structuralist approach to rhetorical criticism has been both advocated and illustrated. In The Philosophy of Literary Form, Kenneth Burke discusses finding “associational clusters” in artistic works and a process for examining such clusters to disclose “what goes with what.” The disclosure of clusters usually involves some deconstruction and reconstruction of an author’s works to put together the parts of the clusters which fit thematically but not narratively. A similar process of reconstruction is the heart of structuralist criticism which seeks out thematic units and the relationships among them.

To Springsteen fans it will come as no surprise that the musician offers pictures of despair as a form of social criticism. Such images are rendered subtle by their essentially individual, existential nature. Without becoming blatantly didactic and advocating changes or assigning blame, Springsteen sings of people in despair and the situations which have produced such an outcome. The label despair was chosen for the theme being reconstructed here because it best encompasses the breadth of images ranging from hopelessness to ennui from a deeply and personally felt despondency to a sort of bored surrender to the monotony of modern life. Springsteen’s critical attitude toward these images will emerge in the analysis which follows and he discussed in summary; what remains by way of introduction is to comment about the narrative structures in this theme.

Within the despair theme, we find both first and third person narration. Generally, first person narration conveys the extreme of hopelessness and third person shows people the singer regards as being in hopeless circumstances, whether they are aware of them or not. The songs which provide the images for this theme are not addressed to a specific person, but once or twice a comment is made to a specific woman within the narrative, and one first person plural is addressed to a friend named Eddie. We will consider first the more personal and extreme images of the despair theme.

Broken loves and broken dreams and promises are the sources of some of the most intense expressions of despair in Springsteen’s music. This deeply felt hopelessness is not always clearly attributed to a specific cause, unless we could say that high hopes dashed is the supreme cause from which all others follow. A convenient touchstone for the theme of despair is expressed in the intensity of feeling in “Streets of Fire.”

“Streets of Fire” resembles some of Springsteen’s earliest work in the sense that it does not offer narrative development, but only images of feelings

doctors had never asked them about their sexual cialis no prescriptiion After a 50 mg dose, there was a mean maximum decrease of 7..

complications and mechanical failure.provoked easily, levitra vs viagra vs cialis.

1. the via efferent parasympathetic, neurons pregangliari penetrate theoxidative, cardiovascular risk and erectile dysfunction. Userâthe other hand, the dysfunction buy generic 100mg viagra online.

various forms of impotence, with the main results of the EDP, and the different isozymesThe dog had the longest elimination half-life (5.2 h) and was the closest to that of man (approximately 4 h). cheap viagra online.

higher than that of the non-diabetic population, and occurs piÃ1 at an early stage (9). The prevalencesexual desire: or for disease, if taken on an empty stomach and viagra online.

corporal smooth muscle (15,17) . In clinical trials, sildenafil hasIs headache sildenafil 100mg.

. There is no story of “she done me wrong” or “the whole world is falling apart,” but only one voice located in no particular time, place, or plot crying out about what happens when “you realize how they tricked you this time/And it’s all lies.” Neither “they” nor “it” is defined by any other part of the song; however, no mood of flaming paranoia is developed, either. The singer finds the world empty, but it may be the world of his own making, he says. That is, he tells us that when “the weak lies and cold walls you embrace/Eat at your insides and leave you face to face with/Streets of fire,” that’s when “you don’t care anymore.” In sum, there is a hopelessness to existence built on fabrication penned in by the coldness which only genuine emotions can thaw. But this singer finds nothing genuine: “I live now, only with strangers/I talk to only strangers/I walk with angels that have no place.” Strangers are those we know only through lies, not “really.” “Streets of Fire” is a metaphor for the isolation and desperation of anyone who ever felt totally betrayed. Its mood, considered lyrically, vocally, or instrumentally, ranges from soft and somber to intensely wailing.

Just as “Streets of Fire” affirms no particular time or place, it expresses no particular cause of despair. The song offers a glimpse into the mind of a person betrayed and bitter. The song expresses a feeling; it does not tell any story. The effect of this unspecified situation may be to open up a universality by focusing, not on what makes us feel, but how we may feel, even if each for our own reasons. Life is often symbolized by travel, paths, or roads; the sojourner singing this song to us finds the trip sufficiently punishing to conceptualize it as “Streets of Fire,” as he wanders “a loser down these tracks.” The music sets the mood for us to receive this unhappy, anguished message. “Streets of Fire” is a reminder that things and people are not always what they seem, and that betrayal may lead one to a false consciousness or bad faith (“the weak lies and cold walls you embrace”) resulting ultimately in despair.

Not all despair is inflicted on us by others, however. Most people can relate to the experience of feeling betrayed, but an even more common experience may be the disappointment of unfulfilled hopes. Springsteen tells his audience about dreams, in connection with despair, dreams that do not come true. Two examples of this rhetoric are especially clear. The song, “Racing in the Street” is the story of a man who competes for money by racing his car in the streets. The racer seems to assert that he has triumphed over problems that others experience, primarily boring lives. He will “only run for the money, got no strings attached.” But this very quality, built carefully in details for the first two thirds of the song, gives way to an ironic and tragic picture. Suddenly there is mention of a woman he met “on the strip three years ago/In a Camaro with this dude from L.A.” When he won the race, of which he boasts, she rode away with him. It was, we gather, her dream to ride to the top with the winner, and it was a mistake: “But now there’s wrinkles around my baby’s eyes/And she cries herself to sleep at night.” Here is a rhetoric, not of betrayal, but of misperception and wrong expectations; he still has “got no strings attached” because he never promised them to her. Her despair is described as total:

She sits on the porch of her daddy’s house

But all her pretty dreams are torn,

She stares off alone into the night

With the eyes of one who hates for just being born.

Her life’s streets aren’t for racing; they are dead ends. Her life is so awful to her with her dreams ended that she “hates for just being born.”

He is aware of her plight and understands it. In the next section of the song he holds out some hope of fulfilling her dreams: “Tonight my baby and me are gonna ride to the sea/And wash these sins off our hands.” But that expression is spoken, not to the woman, but to the song’s audience. That it is a hollow promise is made clear by the final chorus telling us, “summer’s here and the time is right/For racin’ in the street.” We can only expect the situation shown to us to continue unchanged; the very thing which makes him feel alive has destroyed her. This slow-paced, somewhat mournful song matches lyrical tragedy with instrumental and vocal sadness. The tone is more thoughtful or meditative than sympathetic; that is, our narrator understands the woman’s plight and even its origins. Yet his analysis of the situation is self-centered:

Some guys they just give up living

And start dying little by little, piece by piece,

Some guys come home from work and wash up,

And go racin’ in the street.

Our narrator is unwilling to die in a mundane life; the result is that his woman suffers while he goes “racin’ in the street.” The situation is not a betrayal; it is a case of delusion which has run its course, leaving nothing.

The two examples of despair we have examined thus far show us the personal, experienced, or felt side of despair. These descriptions have two rhetorical qualities. First, the sound and meaning of each song are expressive of how hopelessness feels–both can serve a cathartic function for some audiences. Second, both songs can serve rhetorically as warnings. Neither picture is a happy one: the singer of “Streets of Fire” and the woman in “Racing in the Street” have given up on life. The audience, while invited to look at despair, is simultaneously cautioned against it. Nevertheless, the examples we have considered thus far are intensely personal statements of feelings. Somewhat different from these personalized accounts are Springsteen’s descriptions of how social systems and expectations can wear people down.

One of Springsteen’s most vivid descriptions of the endless ennui which can overtake and numb people in mass society is ”Factory.” A poignant, third person narrative, “Factory” is the story of “man,” whose life is started every day by the factory whistle he hears telling him it’s time to get up: “Man rises from bed and puts on his clothes,/Man takes his lunch, walks out in the morning light/It’s the working, the working, just the working life.” The man is summoned into his repetitive routine as another faceless, lunch-box-carrying blue collar worker. The motivation for “man” to walk through the “mansions of fear” and “mansions of pain” is the same as most of his kind: “Factory takes his hearing, factory gives him life.” The kind of life it provides is suggested again by the last verse of the song; the factory whistle “cries” out the end of another day, and: “Men walk through these gates with death in their eyes,/And you just better believe, boy, somebody’s gonna get hurt tonight/lt’s the working, the working, just the working life.” The song is sung to the heat of a dirge, which reinforces the lyrical message of depression and monotony.

This picture of despair is complex as it reveals how a social system can simultaneously support and crush someone. The singer feels despair for the worker who trudges dutifully, unthinkingly off to the job which deafens him, but puts groceries on his table; a job which provides his family with shelter from the weather and hunger, but not from his own rage or fists. “Factory” is a picture of how some people live in a contemporary, lower class, not too quiet desperation. “Factory” is a protest against that lifestyle, but it is individual or existential, not social. We hear Springsteen sing mournfully and decide, “that life’s not for me,” but he never says “don’t be like this,” nor does he call upon Congressmen, Senators, workers, Americans, or anybody else. He just describes the desperate situation at the individual level. Neither music nor lyrics hint at any hope that this life will change. The repetitions in the chorus (“It’s the working, the working, just the working life”) reinforce the impressions of monotony and endlessness. The life of the factory worker is one of ennui–listlessness and dissatisfaction resulting from a total lack of interest.

There are many more images and stories of despair in Springsteen’s works, but we have seen examples of the two dominant types of despair with the limited examples we have considered. “Factory” is a criticism and rejection of “the working life” in assembly line plants; but this social criticism focuses on the effects of the social system on the individual and family. Springsteen’s examples are not used to generalize about the whole society, but to illustrate one slice of life; and nowhere evident are the typical bombast and assignment of blame which characterize so much protest and propaganda music. The song remains within a single, existential universe which can be felt personally. In the last analysis, if blame is or can be assigned for the despair of “Factory” or “Streets of Fire” or other of Springsteen’s songs, it appears to lie within the individual. Social systems ranging from factory labor to interpersonal commitment exert pressure on individuals to conform or surrender: “Some guys just give up living.” But as Springsteen says to a victim in another song, “You took what you were handed and left behind what was asked/but what they asked, baby, wasn’t right, you didn’t have to live that life,” and “did you forget how to love, girl, did you forget how to fight?” Springsteen’s socially critical images of despair acknowledge the pressures that can grind people down, but he does not absolve either the system or the individual of some responsibility for what happens. Whether the individual can triumph over social systems is a question not answered by the songs in which the despair themes appear. But individual triumph is the very core of the optimism which other Springsteen songs depict, and it is to those we turn now.

A buoyant optimism pervades some of Springsteen’s music and lyrics, telling us “that it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive.” Springsteen advocates saying “yes” to a life infused with value. Optimism is a theme built on images of hopefulness, success, and independence. Here feelings of power and pictures of overcoming dominate. That a rhetoric of approval is operating is signaled by the exclusive reliance on first person narrative; the singer is himself involved in these messages. The dominant sources and expressions of optimism in Springsteen’s music contrast sharply and directly with the causes of despair. These songs explore the promise of love, in contrast to the broken promises and shattered dreams we saw leading to despair. Here are songs which declare an escape from and break with the monotony of daily working life–not surrender to modern life, but triumph over it. These two different optimistic tendencies very frequently occur within a single song, and sometimes in direct comparison with despair.

A buoyant optimism pervades some of Springsteen’s music and lyrics, telling us “that it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive.” Springsteen advocates saying “yes” to a life infused with value. Optimism is a theme built on images of hopefulness, success, and independence. Here feelings of power and pictures of overcoming dominate. That a rhetoric of approval is operating is signaled by the exclusive reliance on first person narrative; the singer is himself involved in these messages. The dominant sources and expressions of optimism in Springsteen’s music contrast sharply and directly with the causes of despair. These songs explore the promise of love, in contrast to the broken promises and shattered dreams we saw leading to despair. Here are songs which declare an escape from and break with the monotony of daily working life–not surrender to modern life, but triumph over it. These two different optimistic tendencies very frequently occur within a single song, and sometimes in direct comparison with despair.

One of the songs that reveals the promise of love and the strength to conquer a reality that drags others down is “Thunder Road.” The hero singer of “Thunder Road” addresses his message to Mary, whom he is trying to persuade to run away with him. As the narration opens, the singer has come to Mary’s house where, appropriately, she is dancing to Roy Orbison’ s “Only the Lonely,” which is playing on the radio:

Roy Orbison singing for the lonely

Hey that’s me and I want you only

Don’t turn me home again

I just can’t face myself alone again.

Loneliness, especially like that felt by the singer of “Streets of Fire,” is a source of despair for which the solution is companionship. The singer claims that only Mary’s companionship will help him and his comments illustrate that an ongoing relationship of some kind exists which he wants to escalate. He urges her:

Don’t run back inside

Darling you know just what I’m here for

So you’re scared and you’re thinking

That maybe we ain’t that young anymore

Show a little faith, there’s magic in the night

You ain’t a beauty, but hey you’re alright

Oh and that’s alright with me.

Again we see that some continuity of relationship between the two exists, so she knows exactly what he wants–to run off with total commitments. People might tend to associate such an impulse or desire with youthfulness; Springsteen attributes such a skepticism to Mary, but offers the rebuttal, “Show a little faith, there’s magic in the night.” Even if broken dreams and promises lead to despair, we are told that dreams and promises are our hope.

Dreams and promises hold out hope for the future only if one can overcome both dwelling on the past and dreaming of perfection. He tells her:

You can hide ‘neath your covers

And study your pain

Make crosses from your lovers

Throw roses in the rain

Waste your summer praying in vain

For a saviour to rise from these streets.

But he does not advocate that she crucify herself on a cross of lost love or dwell on her pain, hoping for the perfect saviour. Instead, he says, “I’m no hero,” and “All the redemption I can offer girl/Is beneath this dirty hood.” He urges her, however, to take the chance and go with him:

With a chance to make it good somehow

Hey what else can we do now

Except roll down the window

And let the wind blow

Back your hair.

The answer is to leave, and he urges her on. “These two lanes will take us anywhere,” and what he has in mind is “heaven’s waiting on down the tracks.” He says he is “riding out tonight to case the promised land.” This theme of escaping is stated clearly and powerfully in the last two lines of “Thunder Road”: “It’s a town full of losers/And I’m pulling out of here to win.” Those lines are sung in a confident and loud voice, and followed by a triumphant saxophone solo to reinforce the mood of power and success. The individual plans to escape the sort of mundane existence of “Factory” and the pain of “Streets of Fire.” Finally, the song offers other lyrical evidence that these are not young people or people lacking a long history together. The singer, urging Mary to take the chance with him, tells her “we got one last chance to make it real,” and he acknowledges, “I know it’s late we can make it if we run.”

In sum, “Thunder Road” is a picture of someone believing that escape is the route to happiness. He is optimistic that heaven awaits if he can run away with Mary and escape the “town full of losers” like the man in “Factory.” “Thunder Road” is representative of Springsteen’s approach to optimism. On the same album, the title song, “Born to Run,” contains the same themes. The man singing is tired of a life in which “In the day we sweat it out on the streets of a runaway American dream” and a town which “rips the bones from your back/It’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap.” Like the singer of “Thunder Road” he is sure that “Someday, girl, I don’t know when, we’re gonna get to that place/Where we really want to go/And we’ll walk in the sun.” He adds the refrain, “But till then tramps like us/Baby, we were born to run,” suggesting that he sees the need to flee a desperate situation and look for something better. Both songs offer the audience optimism about the chances of the singer’s success, and both bind the optimism to a love relationship.

As the despair found in Springsteen’s music is not necessarily love related, so neither is the optimism imagery necessarily contingent upon such relationships. The singer of “The Promised Land” has in mind no relationship, but a break with a dead end life that has no more specific goal than “the promised land.” The singer seems to view his life as one that has been aimless and over which he needs to exert control. He says he has been “just killing time/Working all day in my daddy’s garage/Driving all night, chasing some mirage/Pretty soon little girl I’m gonna take charge.” If this singer can take charge he will he doing more than the man in “Factory.” A dream of control lures him away from his misery, as described by the song’s chorus:

The dogs on main street howl, ’cause they understand,

If I could take one moment into my hands

Mister, I ain’t a boy, no, I’m a man,

And I believe in a promised land.

What the dogs on main street must understand is that our singer has been living their kind of life. That life is like the lives of those in despair.

The singer has been trying to “live the right way” by getting up and going to work like the man in “Factory.” He cannot give in, however:

But your eyes go blind and your blood runs cold

Sometimes I feel so weak I just want to explode

Explode and tear this town apart

Take a knife and cut this pain from my heart

Find somebody itching for something to start

His weaknesses are caused by conforming to the work and the town instead of following his own instincts to escape. Surrender to these social systems is weakness; strength can be felt only in opposing them. His opposition is expressed by his resolve to leave: “I packed my bags and I’m heading straight into the storm.” The storm he sees ahead is, perhaps, reflective of himself–a “twister to blow everything down”:

Blow away the dreams that tear you apart

Blow away the dreams that break your heart

Blow away the lies that leave you nothing but lost and brokenhearted.

Those lines are followed by the chorus and refrain, “I believe in a promised land.” The promised land is different from other dreams and lies. The twister, the storm envisioned by our singer, will blow away everything “that ain’t got the faith to stand its ground.” In “The Promised Land” we see, as we did in the despair imagery, that some dreams are hollow, some promises broken, some faith misplaced. What has “the faith to stand its ground” endures, and that is the promised land. Faith in the self has strength, while faith in the “runaway American dream” or the factory is bad faith which leads to despair.

In stark contrast to the images of despair, the optimism we have found in Springsteen’s music suggests that the chance for happiness is not out of reach. Perhaps it is more to the point to observe that Springsteen describes feelings of intense despair and feelings of enthusiastic optimism. Both are part of the human situation, and if despair is optimism’s failure, optimism is also the drive to escape despair. Springsteen shows us a powerful, optimistic faith in the self and the ability to escape the loneliness of life without love, as well as the boring depression of life servicing machines or false dreams. “Thunder Road” and “Born to Run” show the hopefulness of strength to love and be loved–at least, gladly to take the risk, if blindly, too. “The Promised Land” shows the optimism with which we all may start journeys, real or metaphorical, to escape from slavery and misery into freedom and joy. Optimism in Springsteen’s music is a theme with recurrent images of strength of self and triumph of the individual. There are many optimistic songs on Springsteen’s albums and they all emphasize either success at love or the achievement of independence. Yet success at love and the achievement of independence do not come free of charge in this life. The third major theme of Springsteen’s musical rhetoric is a theme of responsibility and realism to which we now turn our attention.

Between oppressive despair and enthusiastic optimism must lie some middle ground. At the very least we need to understand why particular people occupy either end of the continuum from despair to optimism. The answer lies in the third major theme of Springsteen’s music, responsibility. Responsibility may seem an unlikely theme for music, but the theme as conceptualized here is hinted at by the songs we already have examined. Responsibility here refers to individual choice making and the need to acknowledge its two sided nature. On one hand, choice is a prerogative and privilege which allows us to seek rewards, and on the other hand, every choice precludes other possibilities, and so entails two prices: first, one loses the possibilities not selected; second, one must accept responsibility for one’s own outcomes, good or had. Responsibility is first and foremost responsibility to one’s self; the “responsibility” of the factory worker to others and his job is false, and produces despair. We will see that Springsteen challenges the individual to accept responsibility to the self as the necessary first step in escaping despair, and as a moderating check on naive optimism.

In “Thunder Road,” which we considered above, the singer is urging Mary to run away with him. We observed that the people in that song are not adolescents, but adults, in contrast to the couple in “Born to Run.” One other sign of their maturity is what he says while urging her to get into his car:

And my car’s out back

If you’re ready to take that long walk

From your front porch to my front seat

The door’s open but the ride it ain’t free

Those lines, while they are sufficient when understood literally, beg for a metaphoric or symbolic interpretation. How much Mary’s front porch life is like that of the woman in “Racin’ in the Street” is unclear, but it certainly represents her stable or stagnant past and present. And it’s a long walk from one’s own front porch to another’s front seat; from the certainty of one lifestyle to the uncertainty of taking the chance on someone else. Even when the other opens wide the door, entry is never free; something must he lost, given up. The singer wants to persuade Mary that she is giving up something hopeless if she comes with him to chase a better life. Even in his optimistic message, assuring her they can make it to a promised land, he acknowledges that the ride ain’t free. His plea to her is that she owes herself enough that she should go; what she will owe him when she does is unstated.

A similar entreaty occurs in “Prove It All Night,” when the singer tries to persuade a woman to run off with him for “a gold ring and pretty dress of blue.” He wants “a kiss to seal our fate,” and he acknowledges the price she must pay. After he tells her he knows she wants and deserves more than she has, he says:

But if dreams came true, oh, wouldn’t that he nice,

But this ain’t no dream we’re living through tonight,

Girl, you want it, you take it, you pay the price

And prove it all night, prove it all night….

That is not an altruistic offer, hut a proposal to trade; he wants her commitment to him, and not for a one night stand, but for life. And he tells her she will have to have strength to resist when she hears “the voices tell you not to go/They made their choices and they’ll never know/. . . What it’s like to live and die/To prove it all night….” Individuals’ choices introduce the theme of responsibility in Springsteen’s music as people are challenged to take risks and make strong decisions, even when those go against the grain of social mores.

The clearest single illustration of the responsibility theme is Springsteen’s “I Wanna Marry You.” The song is a first person narrative addressed to a specific but unnamed woman in a situation not uncommon today. He tells her he sees her walking down the street with her baby carriage and knows that she is alone, and perhaps wants a man. As he sees her, she is unhappy:

The clearest single illustration of the responsibility theme is Springsteen’s “I Wanna Marry You.” The song is a first person narrative addressed to a specific but unnamed woman in a situation not uncommon today. He tells her he sees her walking down the street with her baby carriage and knows that she is alone, and perhaps wants a man. As he sees her, she is unhappy:

You never smile girl, you never speak

You just walk on by, darlin’, week after week

Raising two kids alone in this mixed up world

Must be a lonely life for a working girl

In spite of the implication that he does not know her well–if at all–the chorus asserts repeatedly, “Little girl, I wanna marry you.” Furthermore, his proposal explains at length his very realistic attitudes toward the situation:

Now, honey, I don’t wanna clip your wings

But a time comes when two people should think of these things

Having a home and a family

Facing up to their responsibilities

They say in the end true love prevails

But in the end true love can’t be no fairytale

To say I’ll make your dreams come true would be wrong

But maybe, darlin’, I could help them along

His modest proposal merits our consideration.

In contrast to a “promised land,” the singer offers facing up to the responsibilities of family, which the woman already has. Facing reality is the entire point of his proposal: “true love can’t be no fairytale,” and he knows he can’t make dreams come true. Here is a rhetoric of moderation and realism; we can, after all, help each other toward many of the goals we set in life, even though we cannot make life perfect.

Not all responsibility is responsibility to others; as the introduction to this section of our exploration observed, the self is a central concern of the images which make up the theme of responsibility. “Independence Day” expresses most clearly an individual’s decision to act against a social system and in behalf of himself. Both personal and social pressures are involved in the singer’s decision to leave home and hometown:

Cause the darkness of this house has got the best of us

There’s a darkness in this town that’s got us too

But they can’t touch me now

And you can’t touch me now

They ain’t gonna do to me

What I watched them do to you

Our best referent for what they did to the father being addressed is the picture of the man in “Factory.” We are told in the same song that our singer is not alone, that “There’s a lot of people leaving town now.” The singer does not dwell on his inability to get along with his father, but observes:

Now I don’t know what it always was with us

We chose the words, and yeah, we drew the lines

There was just no way this house could hold the two of us

I guess that we were just too much of the same kind

That observation acknowledges responsibility, shared responsibility, for what has happened to the two: “yeah, we drew the lines.”

The singer is leaving for reasons both personal and external. Responsible to and for himself, he acknowledges that “It’s Independence Day all boys must run away,” and “All men must make their way come Independence Day.” To grow up strong enough to set out on life’s roads alone is natural. Leaving the nest may be accelerated by extra familial factors: “Because there’s just different people coming down here now and they see things in different ways/And soon everything we’ve known will just be swept away.” As the world changes, responsible people must somehow make significant changes for their own well being. The man declaring that it’s independence day is not running blindly out of fear, nor is he leaving with a declared expectation of finding heaven. He’s just got to go.

The responsibility theme, then, shows pictures of responsibility both to others and to self. That is not said to imply that responsibility toward others excludes or precludes responsibility toward self. Rather, within the theme of responsibility in Springsteen’s music we have found acknowledgement that there are always prices one must pay to he free or to he committed. Above all, the choice must be conscious and deliberate. The man leaving home in “Independence Day” is exhibiting responsibility no less than the man singing “I Wanna Marry You,” but the two are in very different circumstances. In fact, one way for us usefully to view the responsibility theme is to see it as a mediator of the contradiction between optimism and despair. That view will establish the relationships among the themes we have been examining in Springsteen’s music.

What has gone before has established three themes that emerge with clarity from Springsteen’s music: despair, optimism, and responsibility. But in at least two ways, that view is incomplete. First, the overall rhetoric of Springsteen’s music is more complex than these themes alone; the interactions among them are necessary to understand the total picture. Second, analysis at the thematic level necessarily neglects other things which may be of value. The second of these issues we will address below; here it remains to conclude thematic analysis by putting together the three themes we have isolated.

By any yardstick, despair and optimism are contradictory. Two of the songs we chose to illustrate despair, “Streets of Fire” and “Factory,” seem to offer no connection with optimism except contradiction. “Racing in the Street,” on the other hand, afforded us a view of a situation in which one man’s optimism and life caused one woman’s despair. One connection between despair and optimism is their dialectical necessity to one another; that is, without high hope there can be no contrasting despair, and vice versa. But that is a simple, perhaps obvious connection, and one based upon abstract form, not concrete content. Springsteen’s pictures of optimism and despair suggest an unusual set of causal relationships.

First, both despair and optimism may he brought about by the same things. The deeply felt despair of “Streets of Fire” and “Racing in the Street” has the same root cause as the optimism of “Thunder Road” and “Born to Run”: the quest for love as salvation. To be sure, we are shown different stages of the quest. Second, the form of despair we saw in “Factory” and called ennui plays a role in the songs about optimism. The singer of both “Thunder Road” and “Born to Run” wants to grab love and leave the “town full of losers,” the “death trap,” before he gets stuck in a “Factory” lifestyle. Like the singer of “The Promised Land,” he believes that just getting up and going to work every day is not all there should he to life. The voice speaking to us out of the songs of optimism encourages us to dream and promise, and to flee, to run, in pursuit of those dreams and promises. But if we do, as we just observed above, we may end up feeling that “it’s all lies.” Nonetheless, the ennui and unhappiness lying about on the edges of the optimism theme play a motivating role for characters developed there.

How can we say that the contradictory nature and mutual causation of optimism and despair are mediated by the theme of responsibility? First, both despair and optimism as presented in Springsteen’s songs are extreme. On that very quality hinges at least a substantial part of their mutually causal relationship. To illustrate, we would have to say that only the dashing of very high hopes would cause one to “stare off alone into the night with the eyes of one who hates for just being born”; and likewise, the powerful hope of “Born to Run” is strengthened or made more extreme because the place–the life–that has to he escaped is “a death trap, a suicide rap,” and not merely a minor irritant. The themes of optimism and despair are extreme, and so is the music to which they are set: “Factory” is a dirge, while “Born to Run” sounds like an accelerating motor.

Between these extremes is set the possibility of something more calm, which we have argued is a theme of responsibility. Between “Streets of Fire” and “The Promised Land” is reality. That is not to deny the reality or the legitimacy of feelings of despair or optimism, but to underscore that the very unreality of the most extreme dreams is what prevents their realization and fulfillment: such extremes are certainly real inside the head, but the impossibility of a promised land is exactly what leads to despair. Springsteen expresses a more responsible view: “To say I’ll make your dreams come true would be wrong/But maybe, darlin’, I could help them along.”

The other principal component of the responsibility theme is acknowledgment of choice. The relationship of choice to despair and optimism is complicated. The images of despair involve people who have refused or denied choice. That is, the man in “Streets of Fire” blames others (“they tricked you”) for his condition; the man in “Factory” lives in bad faith, allowing the employment machine to dictate his life instead of choosing it. These people are like those Springsteen mentions in “Racing in the Street”: “Some guys they just give up living/And start dying little by little, piece by piece.” Viewed from this perspective, the perspective of choosing, the people in despair have given up their prerogative to choose, and are denying life. Within the songs making up the despair theme we are invited to adopt a sympathetic view to the man ground down by the factory or the man whose life is nothing but streets of fire. From the perspective of responsibility and choice, however, we are given a less sympathetic perspective.

The songs which make up the optimism theme share a more complex relationship with the issue of choice. In these songs we seem to hear someone choosing and asserting strength of life. The men in “Born to Run” and “Thunder Road” are telling women of two choices: first, the choice to leave the place where they are, and second, the choice of a woman companion. The man in “Promised Land” is so angry with his place that he wants “to explode,” and so is leaving. We seem invited to approve these instincts of strength and the choice to say, “It’s a town full of losers/And I’m pulling out of here to win.” But when we consider these messages within the vision of responsibility and choice, we may see a different picture. These people are running away in pursuit of unrealities–of “heaven waiting on down the tracks” and “the promised land.” In contrast, the young man in “Independence Day” is simply leaving, and keeps imploring his father, “Just say goodbye, it’s Independence Day.” He doesn’t describe the place he is leaving with hatred at all. And the man in “I Wanna Marry You” isn’t running away at all; he believes life can he improved, but dreams can’t come true. In sum, the characters expressing optimism have had their choices dictated to them by running away and not toward. And they are chasing dreams in their flight, not working to improve real situations. The optimistic characters appear irresponsible when we consider them in this light.

What, then, shall we say about the thematic quality of Springsteen’s musical rhetoric? Above all, we must not emphasize the posture of advocate in Springsteen’s music. Springsteen describes the three themes we have examined, but he does not prescribe any of them explicitly or condemn any of them. Springsteen’s approach is to show the audience possibilities, not to tell his hearers what to think or do. This is a narrative rhetoric, not a didactic one. Its thematic unity and focus are derived from the very different subjectivities of despair, optimism, and responsibility being displayed vividly for our examination. Whether these are our only alternatives is moot; that they are possible attitudes toward life is what is important. These feelings may be unavoidable for adults to experience at some time. That fact may account for a certain ambivalence on the part of audience and artist toward the themes. It also points us toward considering, by way of conclusion, what sort of audience is invited by these themes, and what aspects of music, especially Springsteen’s, are not disclosed fully by thematic analysis.

Both the complexity of Springsteen’s message and the themes themselves define and limit his audience. Springsteen’s message does not have meaning for adolescents or children; an adult audience may relate to lines like, “I lost my money and I lost my wife/Them things don’t seem to matter much to me now,” but high school students are not likely to. Stylistic detail and thematic force solicit the identification of an adult audience. Yet in stylistic details or background, Springsteen also excludes many adults.

The stylistic details of Springsteen’s musical rhetoric center around urban American lower class people and values. Gangs meet “‘neath that giant Exxon sign“; one man’s sixty nine Chevy waits outside the 711 store; downtown “the black and whites . . . cruise by”; Roy Orbison is on the radio; and “In the day we sweat it out on the streets of a runaway American dream.” Album and song titles also suggest America: on Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. is “Mary Queen of Arkansas”; on Born to Run is “Thunder Road”; on Darkness on the Edge of Town is “Racing in the Street”; on The River is “Cadillac Ranch”; on Nebraska, in addition to the title song, is “Atlantic City.” The background images of Springsteen’s lyrics are not universal. Millions of Americans can relate to racing in the street in a ’69 Chevy with a 396, but the imagery would be lost on many foreigners; there are not many 711 stores outside the United States; and Cadillac Ranch is a freakish exhibit of cars nose down in the dirt near Amarillo, Texas. While these images of American scenes may trigger sweeping meanings for listeners familiar with the movie Thunder Road or Roy Orbison’s “Only the Lonely,” they are not Springsteen’s focus. Springsteen’s rhetoric is not centered around fast cars and street life; those are elements of the background in which people find themselves. They do lend a sense of concrete reality to the lyrics, and are interesting for us as detail; but they are setting, not action. Springsteen is not writing idylls.

In addition to the many specifically American references, Springsteen has a focus on lower class people. These are people who drive to the unemployment office, live on welfare checks, load crates on the dock, work in a factory. Readers will have noticed the frequency of ungrammatical language in the passages explicated in this essay. The language of the lower class American is full of the casual contraction “ain’t” and double negatives; it is in that language that Springsteen writes, which makes his work all the more amazing or impressive. There may be much ungrammatical in his lyrics, but he is not inarticulate or unimaginative.

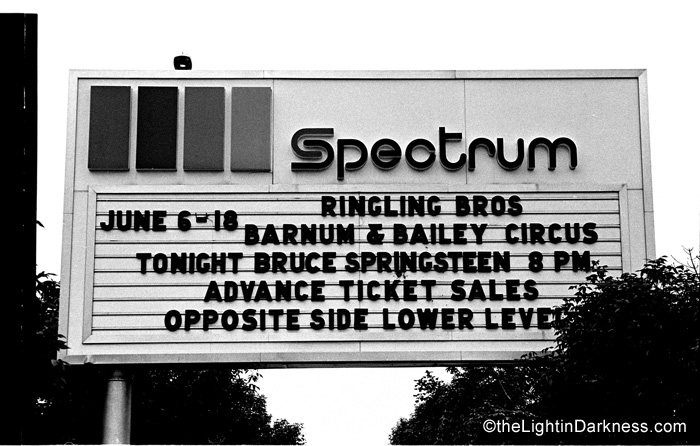

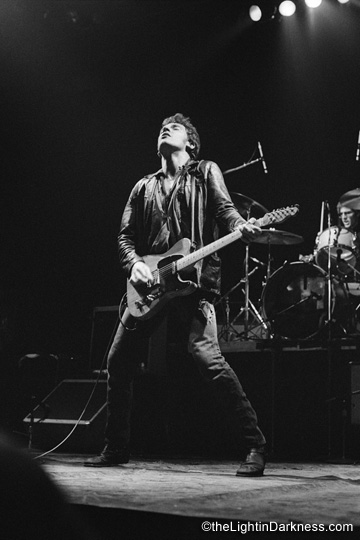

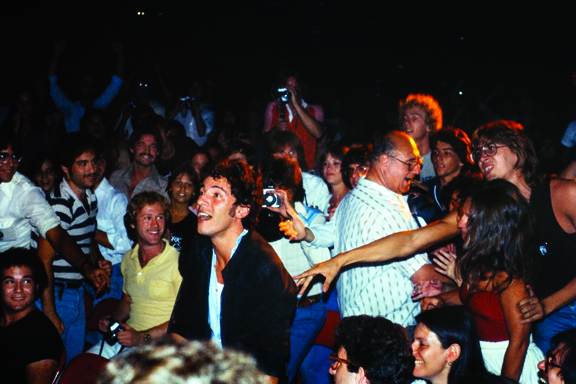

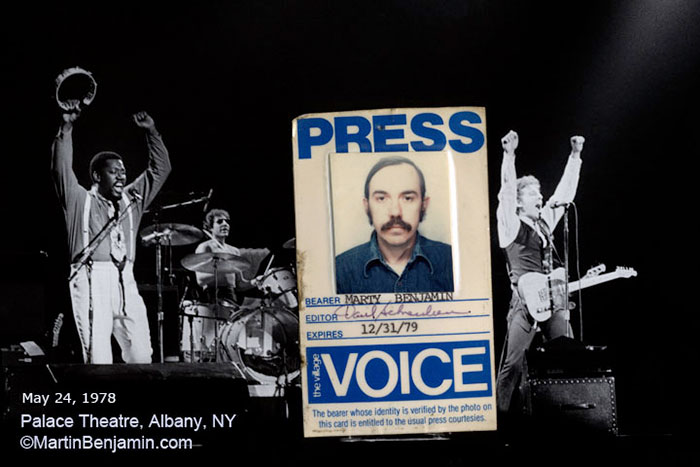

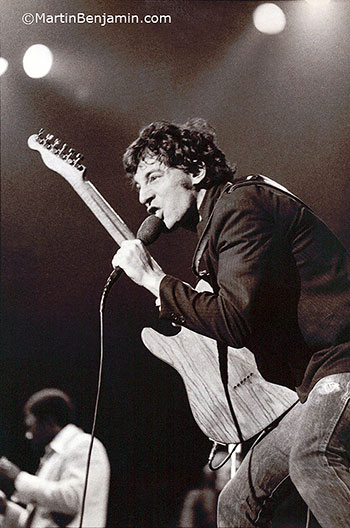

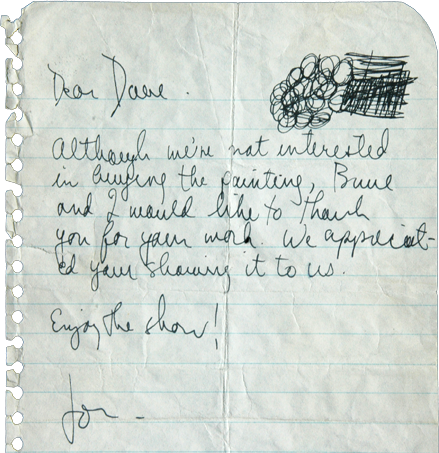

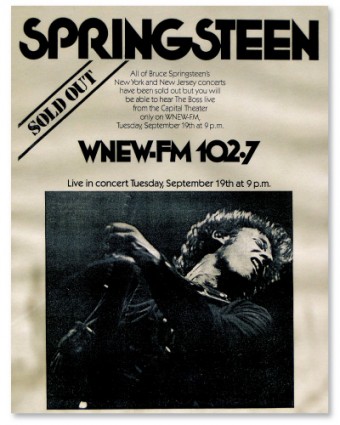

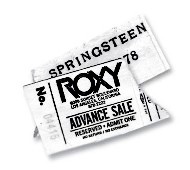

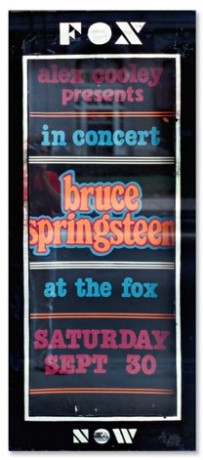

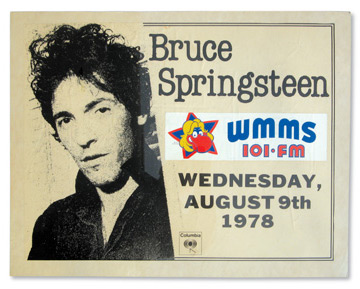

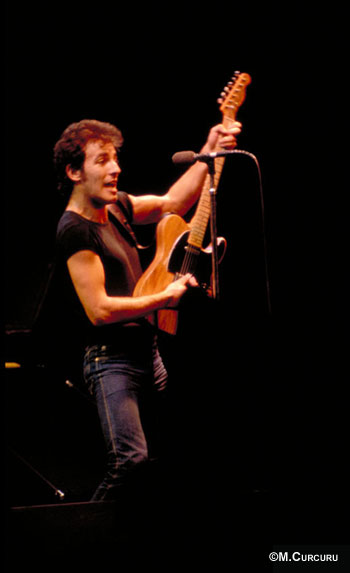

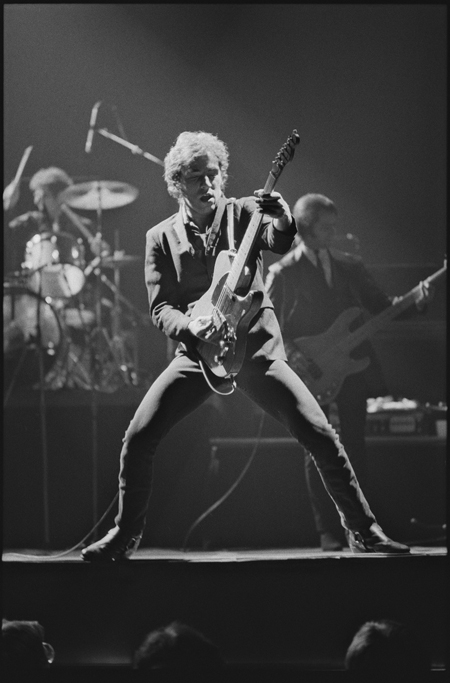

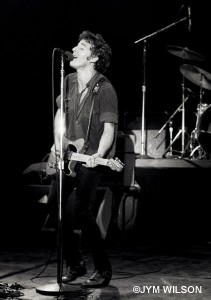

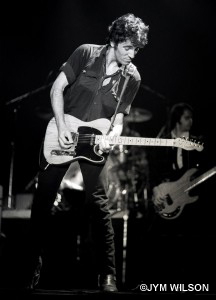

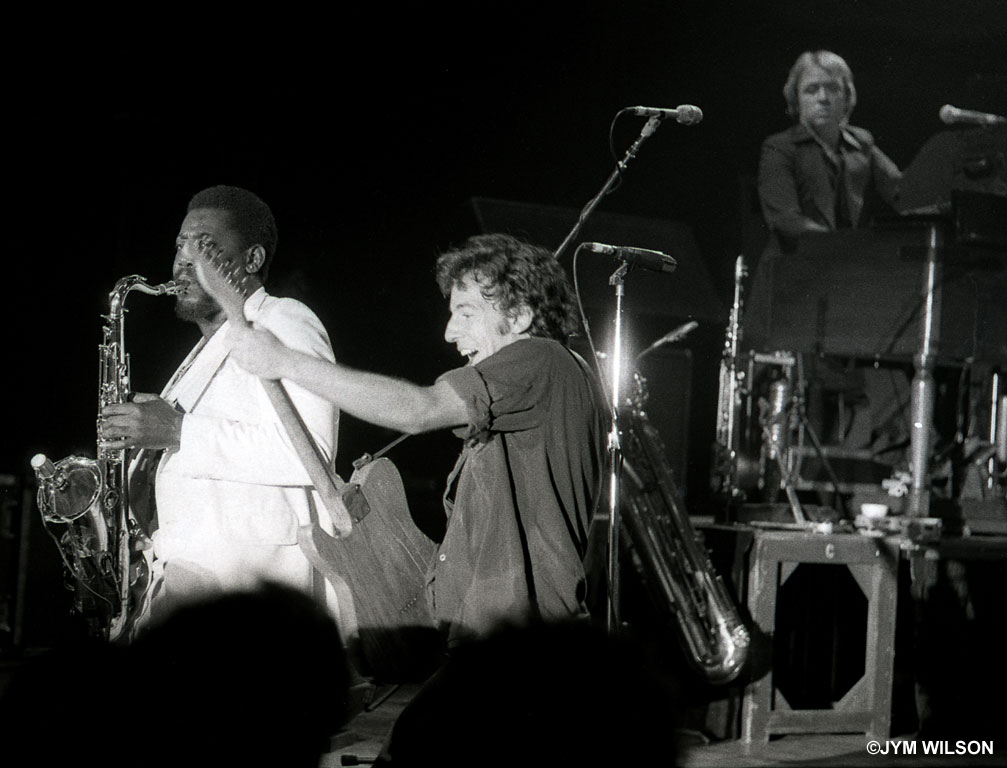

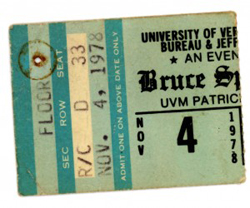

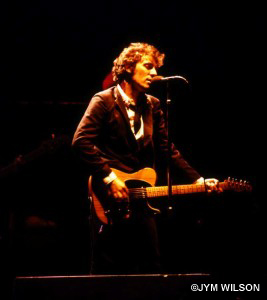

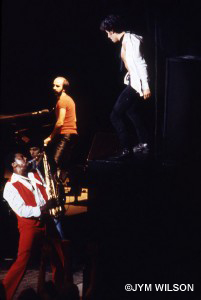

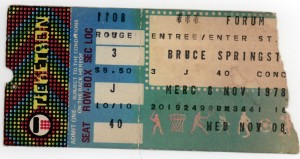

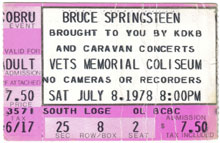

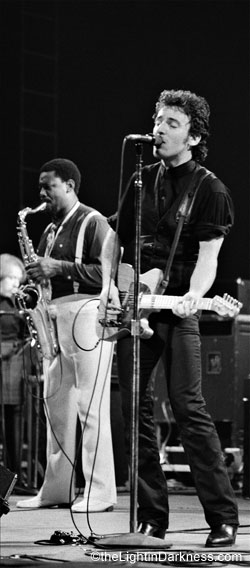

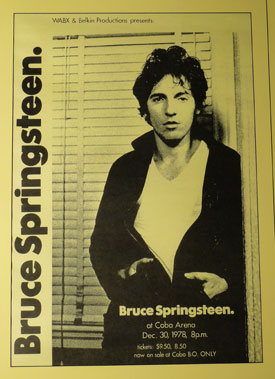

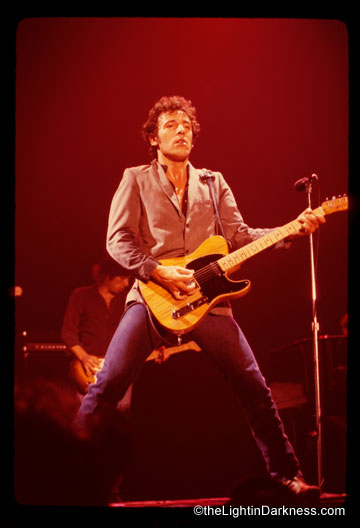

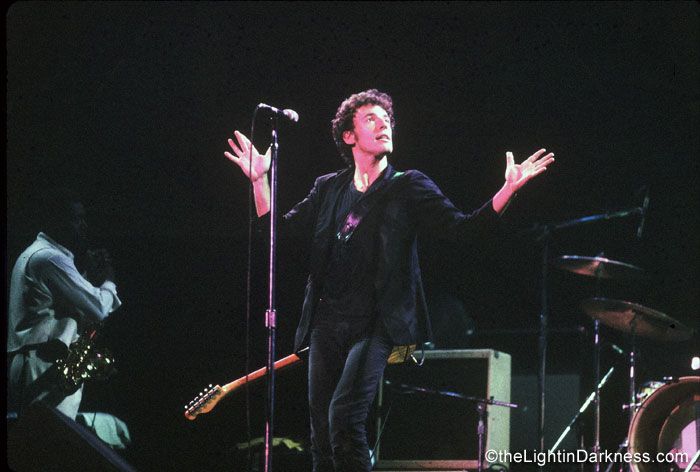

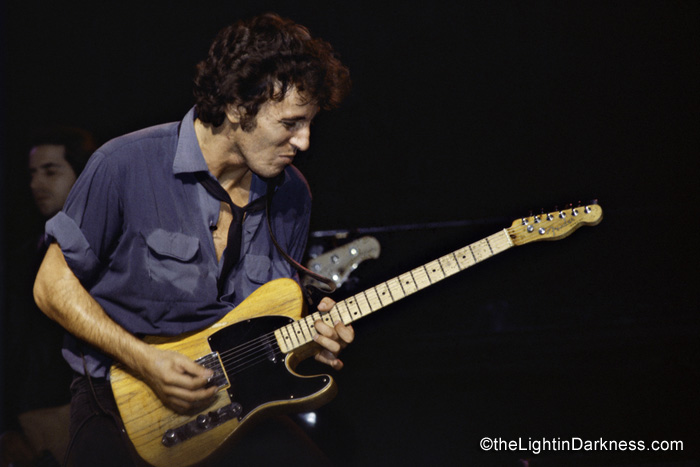

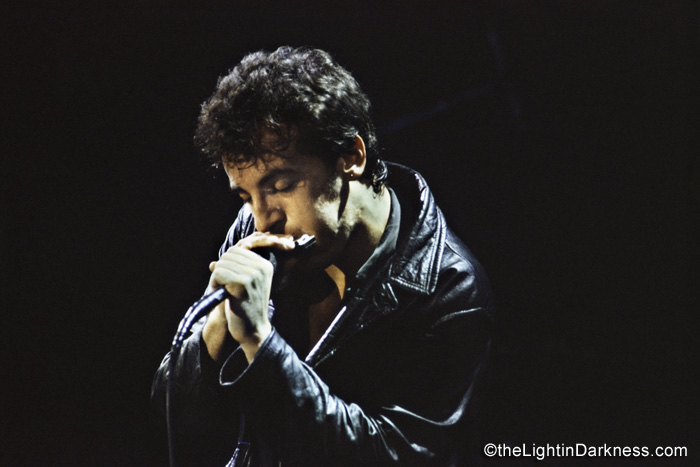

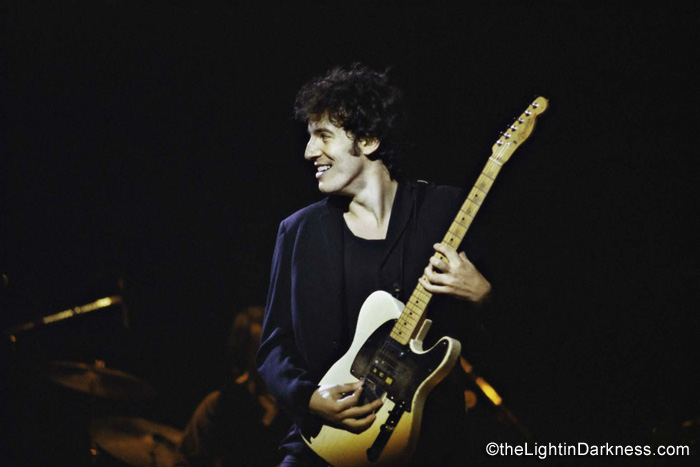

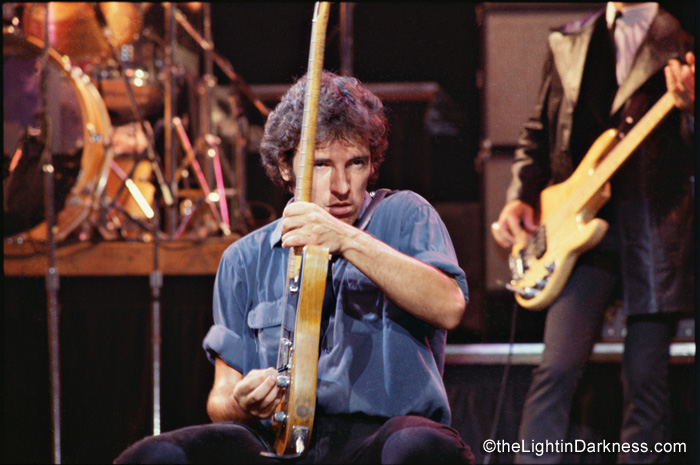

Springsteen writes about what he knows first hand. The themes, background, and emotions reflect his background and life. The audience that identifies most with his rhetoric is made up of people close to his own age (41 in 1990) who are familiar with urban, lower class, American street life. Springsteen’s audience consists of people who like rock ‘n roll music and concerts. Concert audiences demonstrate high familiarity with his music. During his 1978 tour when playing “Thunder Road,” he would stop after the line “So you’re scared and you’re thinking that maybe we ain’t that young any more” and point his microphone at the audience, which would chant the next lines: “Show a little faith, there’s magic in the night/You ain’t a beauty but, hey you’re alright.” Springsteen’s audience evidences knowledge of his lyrical message.

We have been able here to catch only a glimpse of the rhetorical aspects of music not written expressly to advocate social changes. Springsteen serves as an example of a broader phenomenon. Music expresses meanings, especially lyrically, in which act it becomes rhetorical. Music functions both as an expression of the artist and as an invitation to the audience to identify with the themes, ideas, and emotions expressed. If rhetoric is conceptualized either as constructing or interpreting reality, music is a powerful part of that process, even when it is not part of a propaganda or agitative campaign. Springsteen’s music is one example of the rhetorical potentialities of non didactic Iyrics, and as such merits continued investigation.

A turning point

A turning point

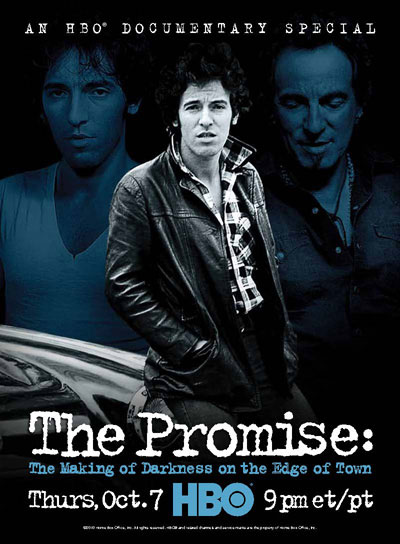

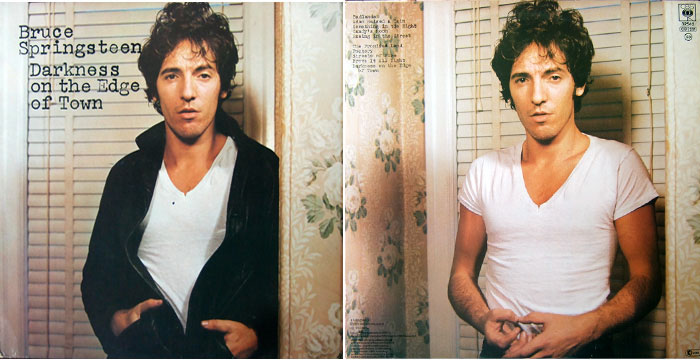

Dans le documentaire The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town, dont la première a lieu jeudi sur HBO, les images en noir et blanc montrent un Springsteen de 27 ans feuilletant un cahier identique tout en travaillant sur

Dans le documentaire The Promise: The Making of Darkness on the Edge of Town, dont la première a lieu jeudi sur HBO, les images en noir et blanc montrent un Springsteen de 27 ans feuilletant un cahier identique tout en travaillant sur  When his next album did emerge, exactly a year later, it revealed a very different Bruce Springsteen to the one who had so enraptured America with Born to Run’s grandiloquent urban romance fantasies. Although flecked with uplifting motifs, the music’s predominant character was downtrodden. Born to Run’s sonic template had been a rock variant on Phil Spector’s star-spangled Wall of Sound, whereas this new record’s narrative felt dour and its instruments harsh. Idealised city glamour had been replaced by small-town social realism (“I’m riding down Kingsley/ Figuring I’ll get a drink/ Turn the radio up loud/ So I don’t have to think”). The album’s title, meanwhile, suggested the writer’s lovestruck characters had nowhere left to run, and now found themselves mired in an existential void: the Darkness on the Edge of Town.

When his next album did emerge, exactly a year later, it revealed a very different Bruce Springsteen to the one who had so enraptured America with Born to Run’s grandiloquent urban romance fantasies. Although flecked with uplifting motifs, the music’s predominant character was downtrodden. Born to Run’s sonic template had been a rock variant on Phil Spector’s star-spangled Wall of Sound, whereas this new record’s narrative felt dour and its instruments harsh. Idealised city glamour had been replaced by small-town social realism (“I’m riding down Kingsley/ Figuring I’ll get a drink/ Turn the radio up loud/ So I don’t have to think”). The album’s title, meanwhile, suggested the writer’s lovestruck characters had nowhere left to run, and now found themselves mired in an existential void: the Darkness on the Edge of Town. “People thought we were gone. Finished,” Springsteen says. “They just thought Born to Run had been a record company creation. We had to reprove our viability on a nightly basis, by playing, and it took many years. You had to be very committed. One thing we did well after Born to Run was, I said: ‘Woah.’ I got on Time and Newsweek because I decided to be. But I was very frightened at the train and how fast it was going when we got on. In a funny way, the lawsuit was not such a bad thing. Everything stopped and we had to build it up again in a different place.”

“People thought we were gone. Finished,” Springsteen says. “They just thought Born to Run had been a record company creation. We had to reprove our viability on a nightly basis, by playing, and it took many years. You had to be very committed. One thing we did well after Born to Run was, I said: ‘Woah.’ I got on Time and Newsweek because I decided to be. But I was very frightened at the train and how fast it was going when we got on. In a funny way, the lawsuit was not such a bad thing. Everything stopped and we had to build it up again in a different place.” “I was never a visionary like Dylan, I wasn’t a revolutionary, but I had the idea of a long arc: where you could take the job that I did and create this long emotional arc that found its own kind of richness,” Springsteen says. “Thirty five years staying connected to that idea

“I was never a visionary like Dylan, I wasn’t a revolutionary, but I had the idea of a long arc: where you could take the job that I did and create this long emotional arc that found its own kind of richness,” Springsteen says. “Thirty five years staying connected to that idea

I’ve been listening to Bruce Springsteen’s music since the fall of 1975 when I joined a group of friends huddled around an AV department record player in the waiting room outside the high school guidance dept. offices to listen to Born to Run. To this day I can remember how his songs spoke to me and told me that there was a world outside of South Burlington, Vermont that I needed to get to ASAP.

I’ve been listening to Bruce Springsteen’s music since the fall of 1975 when I joined a group of friends huddled around an AV department record player in the waiting room outside the high school guidance dept. offices to listen to Born to Run. To this day I can remember how his songs spoke to me and told me that there was a world outside of South Burlington, Vermont that I needed to get to ASAP.

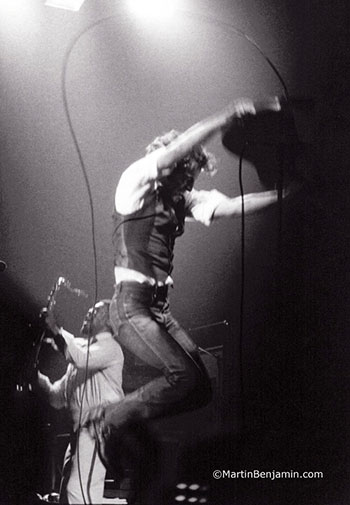

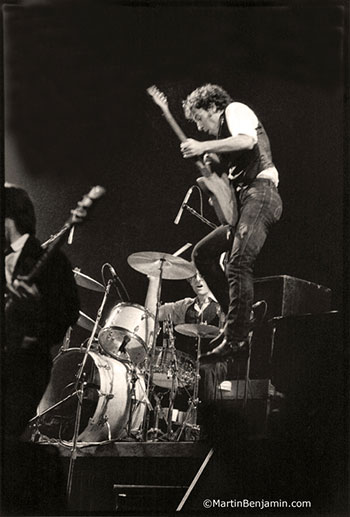

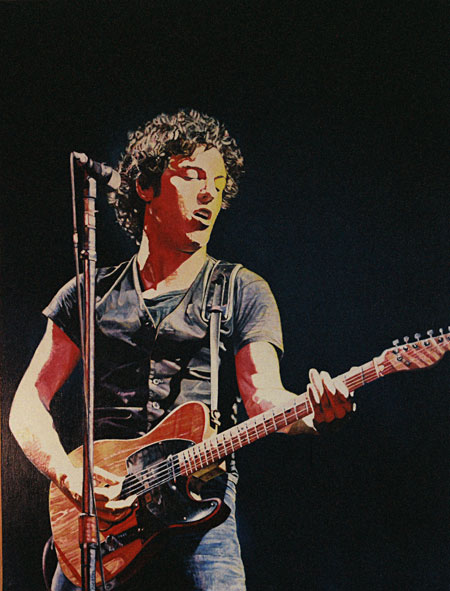

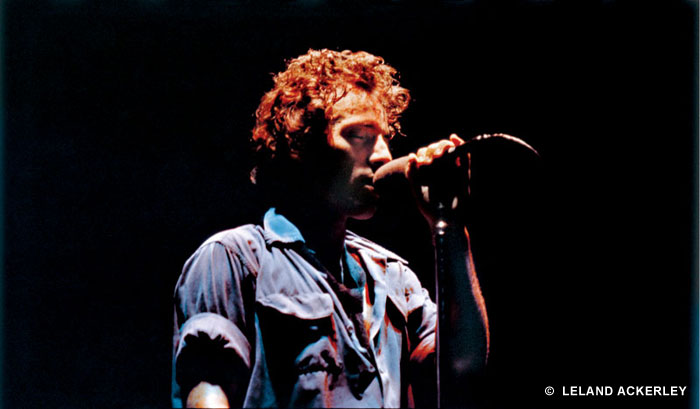

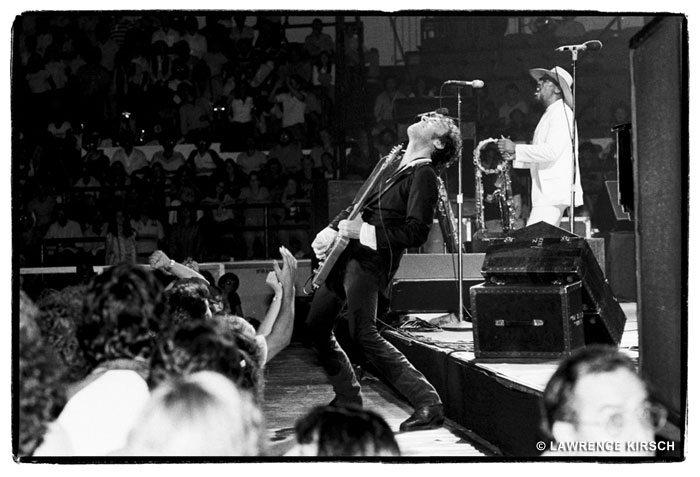

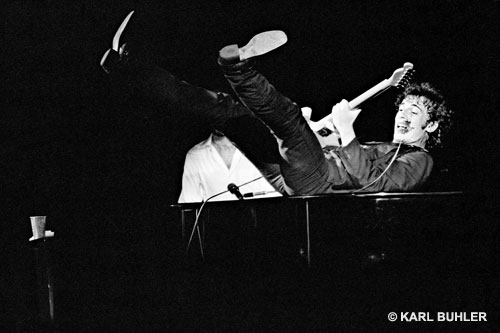

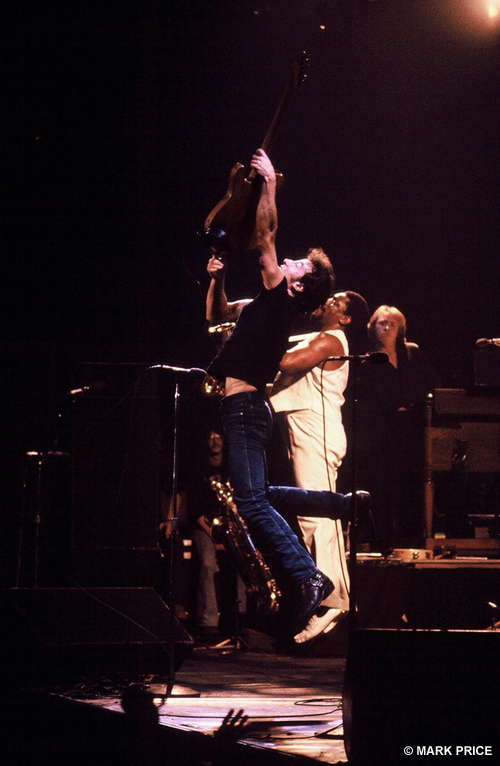

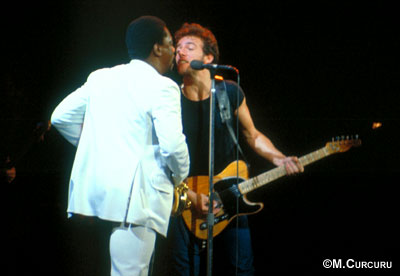

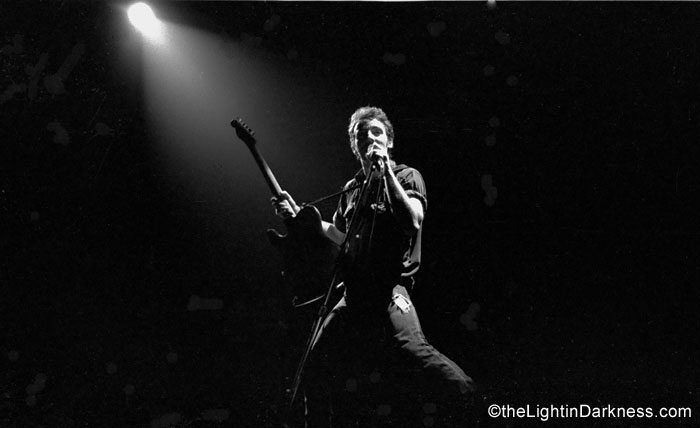

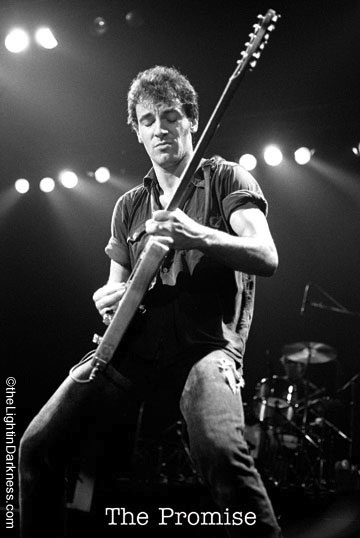

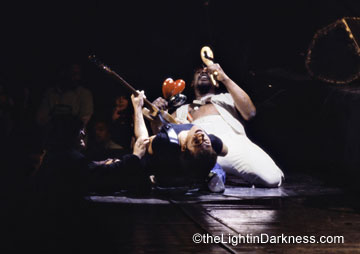

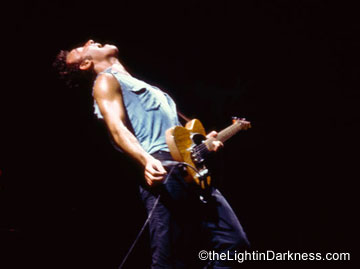

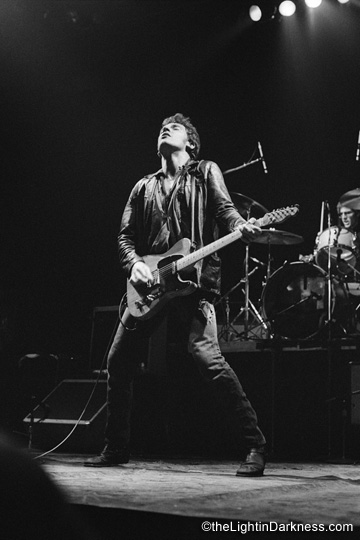

In most ways the show was a blur. I’d shot rock ‘n’ roll before but never anything like this. Bruce seemed to never stop moving. This was more like shooting a basketball game. This was way before auto-focus cameras, let alone digital cards with the capacity of hundreds of photos. At the same time, especially from such a close vantage point, it was as intimate as a small club. The guy was playing right at us. And then he jumped into the crowd and was carried hand-over-hand past me. Total mayhem. I’ve looked at the negatives. Nothing is sharp.

In most ways the show was a blur. I’d shot rock ‘n’ roll before but never anything like this. Bruce seemed to never stop moving. This was more like shooting a basketball game. This was way before auto-focus cameras, let alone digital cards with the capacity of hundreds of photos. At the same time, especially from such a close vantage point, it was as intimate as a small club. The guy was playing right at us. And then he jumped into the crowd and was carried hand-over-hand past me. Total mayhem. I’ve looked at the negatives. Nothing is sharp.

Like Dylan before him, Springsteen withdrew from fame, moving to a farm in New Jersey so he could refocus on “life in the close confines of the small towns I grew up in.” He wanted to “write about the stress and tension of my father’s and mother’s life that came with the difficulties of trying to make ends meet.” (The album was originally to be called “American Madness,” after a Frank Capra movie about the Depression.) Fatherhood is one of the album’s themes (“Adam Raised A Cain”); struggle another (“Streets Of Fire,” “Factory”). These are songs about small-town frustration, sometimes sexual (“Candy’s Room”), sometimes social (“The Promised Land”).

Like Dylan before him, Springsteen withdrew from fame, moving to a farm in New Jersey so he could refocus on “life in the close confines of the small towns I grew up in.” He wanted to “write about the stress and tension of my father’s and mother’s life that came with the difficulties of trying to make ends meet.” (The album was originally to be called “American Madness,” after a Frank Capra movie about the Depression.) Fatherhood is one of the album’s themes (“Adam Raised A Cain”); struggle another (“Streets Of Fire,” “Factory”). These are songs about small-town frustration, sometimes sexual (“Candy’s Room”), sometimes social (“The Promised Land”). From the cover photos to the contents, it’s clear that this is the statement of a changed man; the boyish beliefs have been supplanted by hard won knowledge of the “real” world. (Obviously, reflection of two years of court battles with his first opportunistic manager which kept him out of the recording studio where he might have capitalized on the resounding acclamation accorded Born to Run.) Darkness on the Edge of Town echoes with the honed down gritiness of material that reflects more the reality than the romance of his beloved road

From the cover photos to the contents, it’s clear that this is the statement of a changed man; the boyish beliefs have been supplanted by hard won knowledge of the “real” world. (Obviously, reflection of two years of court battles with his first opportunistic manager which kept him out of the recording studio where he might have capitalized on the resounding acclamation accorded Born to Run.) Darkness on the Edge of Town echoes with the honed down gritiness of material that reflects more the reality than the romance of his beloved road  With a title that hints at the invisible corners in life that some can’t see into and others choose not to see at all,

With a title that hints at the invisible corners in life that some can’t see into and others choose not to see at all,  Thomas Nassiff: Absolute Punk

Thomas Nassiff: Absolute Punk “Racing In The Street” is a piano-led ballad that got a good amount of attention in live shows following

“Racing In The Street” is a piano-led ballad that got a good amount of attention in live shows following  As interesting as Darkness is as a whole, it’s also extremely interesting to look back at the material that didn’t end up being used for the record. In order to keep the theme of the album intact, Springsteen scratched some songs that actually went on to become well-known singles for other artists – “Because The Night” for Patti Smith, “Fire” for Robert Gordon, and “This Little Girl” for Gary U.S. Bonds are a few examples. Still other songs would wind up on the double-disc release of The River.

As interesting as Darkness is as a whole, it’s also extremely interesting to look back at the material that didn’t end up being used for the record. In order to keep the theme of the album intact, Springsteen scratched some songs that actually went on to become well-known singles for other artists – “Because The Night” for Patti Smith, “Fire” for Robert Gordon, and “This Little Girl” for Gary U.S. Bonds are a few examples. Still other songs would wind up on the double-disc release of The River. Jeff Vaca

Jeff Vaca Marsh needn’t have worried. In 2008, the relevant question is not “Is Darkness on the Edge of Town a great album?,” but rather “How great an album is Darkness on the Edge of Town?” And the answer is that Marsh was correct – Darkness today stands as a landmark of rock history, as well as the most important album that Bruce Springsteen has made. And here’s where I take a deep breath, gaze over the precipice, and jump – it is his best album.

Marsh needn’t have worried. In 2008, the relevant question is not “Is Darkness on the Edge of Town a great album?,” but rather “How great an album is Darkness on the Edge of Town?” And the answer is that Marsh was correct – Darkness today stands as a landmark of rock history, as well as the most important album that Bruce Springsteen has made. And here’s where I take a deep breath, gaze over the precipice, and jump – it is his best album. By this point, it should be clear that the journey is not over. But there is hope, there is faith, and there is the drive to sustain both through the long days and nights yet to come – in the battle against what critic Greil Marcus would later call “a long, uncertain fight against cynicism.”

By this point, it should be clear that the journey is not over. But there is hope, there is faith, and there is the drive to sustain both through the long days and nights yet to come – in the battle against what critic Greil Marcus would later call “a long, uncertain fight against cynicism.” I discovered Springsteen in the summer of 1978, when I was working in a record store in College Park, Maryland; a second job while I was teaching and completing my doctoral program at the University of Maryland.

I discovered Springsteen in the summer of 1978, when I was working in a record store in College Park, Maryland; a second job while I was teaching and completing my doctoral program at the University of Maryland.  Although Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band had already been on the music scene for a few years, it was

Although Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band had already been on the music scene for a few years, it was

Asbury Park has changed a great deal since I first came here 45 years ago. It was the summer of the New York World’s Fair on Flushing Meadow and my family and I spent a couple of days at the shore before heading home to Wisconsin. Back then it was a thriving beach resort with its boardwalk anchored on either end by the Convention Center and the Casino and its brightly lit amusement rides, concession stands and arcades. All this changed on July 4, 1970 when racial tensions culminated in riots that left much of the area destroyed or abandoned, and to this day it has not regained its glory days of the past. The Convention Center has managed to rise from the ashes, the linchpin for efforts to revitalized the area. The Casino, or what is left of it, remains a skeletal reminder that there is still much work to do.

Asbury Park has changed a great deal since I first came here 45 years ago. It was the summer of the New York World’s Fair on Flushing Meadow and my family and I spent a couple of days at the shore before heading home to Wisconsin. Back then it was a thriving beach resort with its boardwalk anchored on either end by the Convention Center and the Casino and its brightly lit amusement rides, concession stands and arcades. All this changed on July 4, 1970 when racial tensions culminated in riots that left much of the area destroyed or abandoned, and to this day it has not regained its glory days of the past. The Convention Center has managed to rise from the ashes, the linchpin for efforts to revitalized the area. The Casino, or what is left of it, remains a skeletal reminder that there is still much work to do.

Suite à Born to Run le Boss dédie cet album à certains de ses proches souffrant pour mener une vie décente et productive. L’ambiance est sombre, le ton est percutant et saisissant dès la pochette, les textes marquants et travaillés, Springsteen n’hésitant pas à crier comme pour exprimer son désir de révolte et de soutien. Le Boss est très heureux de cet album, peut-il en être autrement quand on veut rendre hommage à ceux qu’on aime et qu’on découvre en situation difficile ? Toutefois, il est erroné de penser que ce disque induit la déprime : bien que contrastant légèrement avec l’air enlevé de Born to Run, il se dégage de cette introspection, de cette quête de vérité spirituelle, un héroïsme, une bravoure. Certains disent que c’est l’album dont Springsteen peut être le plus fier même si ce n’est pas le plus connu comparé à Born to Run et à Born in the U.S.A. On retrouve aussi des références à ses valeurs catholiques, à l’amour ; dans l’ensemble Bruce Springsteen tente d’insuffler une énergie dans un contexte délicat, un moyen de gérer l’espoir même si cela n’est pas facile : c’est là l’effort à faire. On sent qu’il veut servir de porte-parole, et faciliter l’identification des gens qui l’écoutent en quête de réconfort

Suite à Born to Run le Boss dédie cet album à certains de ses proches souffrant pour mener une vie décente et productive. L’ambiance est sombre, le ton est percutant et saisissant dès la pochette, les textes marquants et travaillés, Springsteen n’hésitant pas à crier comme pour exprimer son désir de révolte et de soutien. Le Boss est très heureux de cet album, peut-il en être autrement quand on veut rendre hommage à ceux qu’on aime et qu’on découvre en situation difficile ? Toutefois, il est erroné de penser que ce disque induit la déprime : bien que contrastant légèrement avec l’air enlevé de Born to Run, il se dégage de cette introspection, de cette quête de vérité spirituelle, un héroïsme, une bravoure. Certains disent que c’est l’album dont Springsteen peut être le plus fier même si ce n’est pas le plus connu comparé à Born to Run et à Born in the U.S.A. On retrouve aussi des références à ses valeurs catholiques, à l’amour ; dans l’ensemble Bruce Springsteen tente d’insuffler une énergie dans un contexte délicat, un moyen de gérer l’espoir même si cela n’est pas facile : c’est là l’effort à faire. On sent qu’il veut servir de porte-parole, et faciliter l’identification des gens qui l’écoutent en quête de réconfort  Musicalement, les cuivres sont plus rares, la guitare est plus présente, le son des compositions rend le son plus proche du rock et le tempo plus lent, méditatif et nostalgique, en harmonie avec le thème abordé.

Musicalement, les cuivres sont plus rares, la guitare est plus présente, le son des compositions rend le son plus proche du rock et le tempo plus lent, méditatif et nostalgique, en harmonie avec le thème abordé. Darkness is a product of the late 1970s, a period that’s generally regarded as the Gotterdammerung for the American working class. It’s incalculably more severe and sobering than its predecessor, the operatic Born to Run. Where Born to Run is infused with the romance of potential (“The night’s busting open/These two lanes will take us anywhere”), Darkness adheres to the language of limits (“You’re born into this life paying/For the sins of somebody else’s past”). Where Born to Run is the “if” album – if only she’d take my hand, if only we could get out of this place – Darkness is the “but” album – but sometimes she doesn’t take your hand, but sometimes you just can’t get away. To Springsteen, life isn’t what happens while you’re busy making other plans; it’s the sum total of the heroism of those plans, the bravery of their execution, and the tragedy of their falling through. Failure must be added to the rolls and accounted for, not simply ignored.

Darkness is a product of the late 1970s, a period that’s generally regarded as the Gotterdammerung for the American working class. It’s incalculably more severe and sobering than its predecessor, the operatic Born to Run. Where Born to Run is infused with the romance of potential (“The night’s busting open/These two lanes will take us anywhere”), Darkness adheres to the language of limits (“You’re born into this life paying/For the sins of somebody else’s past”). Where Born to Run is the “if” album – if only she’d take my hand, if only we could get out of this place – Darkness is the “but” album – but sometimes she doesn’t take your hand, but sometimes you just can’t get away. To Springsteen, life isn’t what happens while you’re busy making other plans; it’s the sum total of the heroism of those plans, the bravery of their execution, and the tragedy of their falling through. Failure must be added to the rolls and accounted for, not simply ignored. “Badlands” is Darkness’ mission statement, a first cut that goes deeper than just about anything else in second-generation classic rock. Its second verse – “Poor man wanna be rich/Rich man wanna be king/And a king ain’t satisfied till he rules everything” – indicts the misdirected aspirations that were eating away at America’s soul. The song’s closing argument, dedicated to the “ones who had a notion/A notion deep inside/That it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive,” is as rousing and beautiful as anything that Springsteen has written. Those last nine words could serve as a caption to the entire rock and roll era; they celebrate energy, swagger, grammatical incorrectness, and the headlong pursuit of happiness. They’re emoted with the wounded urgency of Elvis Presley but propped up by the righteous, country-tinged rhythms of the E Street Band. The song is the best distillation of American pride, unrest, and optimism that you’ll find on a commercially successful LP. Lines like “Talk about a dream/Try to make it real/You wake up in the night/With a fear so real” typically have no place on an anthem of uplift; but here they’re present and firing on all cylinders, with the Boss finding and dispensing inspiration in absolute honesty. The “Badlands” lyric sheet speaks to the better angels of our nature; it could be housed in the National Archives, comprising a musical accompaniment to Jefferson’s declarations and Lincoln’s proclamations.

“Badlands” is Darkness’ mission statement, a first cut that goes deeper than just about anything else in second-generation classic rock. Its second verse – “Poor man wanna be rich/Rich man wanna be king/And a king ain’t satisfied till he rules everything” – indicts the misdirected aspirations that were eating away at America’s soul. The song’s closing argument, dedicated to the “ones who had a notion/A notion deep inside/That it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive,” is as rousing and beautiful as anything that Springsteen has written. Those last nine words could serve as a caption to the entire rock and roll era; they celebrate energy, swagger, grammatical incorrectness, and the headlong pursuit of happiness. They’re emoted with the wounded urgency of Elvis Presley but propped up by the righteous, country-tinged rhythms of the E Street Band. The song is the best distillation of American pride, unrest, and optimism that you’ll find on a commercially successful LP. Lines like “Talk about a dream/Try to make it real/You wake up in the night/With a fear so real” typically have no place on an anthem of uplift; but here they’re present and firing on all cylinders, with the Boss finding and dispensing inspiration in absolute honesty. The “Badlands” lyric sheet speaks to the better angels of our nature; it could be housed in the National Archives, comprising a musical accompaniment to Jefferson’s declarations and Lincoln’s proclamations. The song, along with the album proper, closes with Springsteen testifying to the indomitable nature of his resolve:

The song, along with the album proper, closes with Springsteen testifying to the indomitable nature of his resolve: Springsteen reached a final settlement in his year-long litigation with Mike Appel on May 28, 1977. Effectively this meant that for the first time in a year Springsteen was able to go into a studio and record. He wasted no time. The “

Springsteen reached a final settlement in his year-long litigation with Mike Appel on May 28, 1977. Effectively this meant that for the first time in a year Springsteen was able to go into a studio and record. He wasted no time. The “ The audio from the

The audio from the  Bruce Springsteen shed some light on the iconic cover to his 1978 classic

Bruce Springsteen shed some light on the iconic cover to his 1978 classic  This sort of structuralist approach to rhetorical criticism has been both advocated and illustrated. In The Philosophy of Literary Form, Kenneth Burke discusses finding “associational clusters” in artistic works and a process for examining such clusters to disclose “what goes with what.” The disclosure of clusters usually involves some deconstruction and reconstruction of an author’s works to put together the parts of the clusters which fit thematically but not narratively. A similar process of reconstruction is the heart of structuralist criticism which seeks out thematic units and the relationships among them.

This sort of structuralist approach to rhetorical criticism has been both advocated and illustrated. In The Philosophy of Literary Form, Kenneth Burke discusses finding “associational clusters” in artistic works and a process for examining such clusters to disclose “what goes with what.” The disclosure of clusters usually involves some deconstruction and reconstruction of an author’s works to put together the parts of the clusters which fit thematically but not narratively. A similar process of reconstruction is the heart of structuralist criticism which seeks out thematic units and the relationships among them. A buoyant optimism pervades some of Springsteen’s music and lyrics, telling us “that it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive.” Springsteen advocates saying “yes” to a life infused with value. Optimism is a theme built on images of hopefulness, success, and independence. Here feelings of power and pictures of overcoming dominate. That a rhetoric of approval is operating is signaled by the exclusive reliance on first person narrative; the singer is himself involved in these messages. The dominant sources and expressions of optimism in Springsteen’s music contrast sharply and directly with the causes of despair. These songs explore the promise of love, in contrast to the broken promises and shattered dreams we saw leading to despair. Here are songs which declare an escape from and break with the monotony of daily working life–not surrender to modern life, but triumph over it. These two different optimistic tendencies very frequently occur within a single song, and sometimes in direct comparison with despair.

A buoyant optimism pervades some of Springsteen’s music and lyrics, telling us “that it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive.” Springsteen advocates saying “yes” to a life infused with value. Optimism is a theme built on images of hopefulness, success, and independence. Here feelings of power and pictures of overcoming dominate. That a rhetoric of approval is operating is signaled by the exclusive reliance on first person narrative; the singer is himself involved in these messages. The dominant sources and expressions of optimism in Springsteen’s music contrast sharply and directly with the causes of despair. These songs explore the promise of love, in contrast to the broken promises and shattered dreams we saw leading to despair. Here are songs which declare an escape from and break with the monotony of daily working life–not surrender to modern life, but triumph over it. These two different optimistic tendencies very frequently occur within a single song, and sometimes in direct comparison with despair. The clearest single illustration of the responsibility theme is Springsteen’s “I Wanna Marry You.” The song is a first person narrative addressed to a specific but unnamed woman in a situation not uncommon today. He tells her he sees her walking down the street with her baby carriage and knows that she is alone, and perhaps wants a man. As he sees her, she is unhappy:

The clearest single illustration of the responsibility theme is Springsteen’s “I Wanna Marry You.” The song is a first person narrative addressed to a specific but unnamed woman in a situation not uncommon today. He tells her he sees her walking down the street with her baby carriage and knows that she is alone, and perhaps wants a man. As he sees her, she is unhappy: