He walked alone with a single spotlight following him to a stool that was placed downstage nearly at the lip of platform. The audience around me erupted with glee, a vocal lava that spewed forth a series of BRUCE!!!!!!!!!!! The refrains echoed off the old arena walls, which basketballer Larry Bird once called, “an oversized gym.”

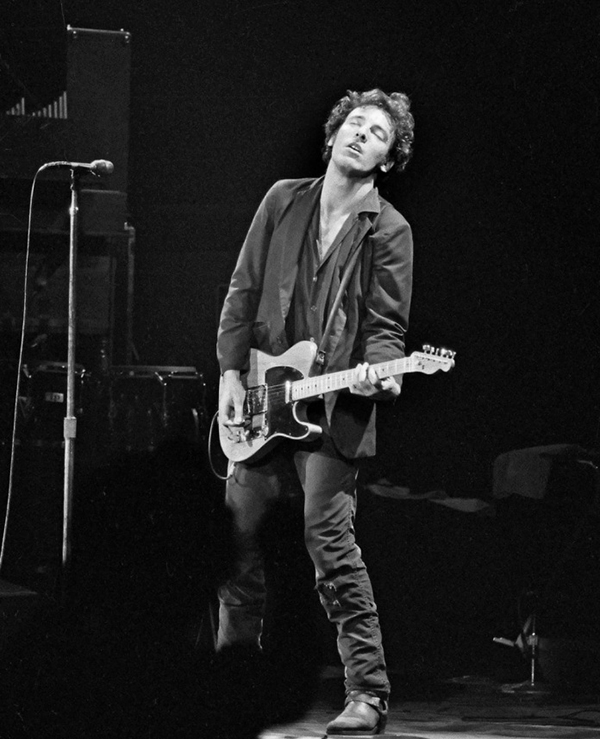

Despite the mayhem, he sat down quietly in front of a boom mike and an electric guitar placed beside in its own stand like a gun in its holster. At first glance, he seemed like a scruffy waif who could use a little food. Of course, there is nothing in a caterpillar that remotely suggests that it will turn into a butterfly. Nevertheless, the young man who just wandered onto an expansive stage holding a newspaper had inexplicably captured the attention of 15,000 people instantaneously.

As the cries continued to resound throughout archaic Boston Garden, a bulging, shabby, and anachronistic edifice, the spry performer took out that day’s edition of The Boston Globe, September 25, 1978, and began to methodically peruse through it. The audience became transfixed and began to hush themselves to a semblance of quietude. In the meantime, the urchin on stage continued to read the local daily newspaper as thousands looked on with reverent silence.

Suddenly, as if struck by an electrical surge, Bruce Springsteen shot upright, hurled The Globe skyward, lunged for his guitar, grabbed it in one fell swoop, and then screeched into the mike, “Have you heard the news? Everybody’s rockin’ tonight!”

13 months after the death of the first King of Rock ‘n Roll, we who were in Boston Garden at that moment recognized that standing before us was Elvis Presley’s successor. For the rest of the evening, those of us in the old arena hardly sat. We danced, sweated, jumped, and swayed along with a performer and his band who seemed immortal at that moment.

In retrospect, this was just another evening in an extraordinary year that would prove to be Bruce Springsteen’s analog to Picasso’s Blue Period. After a three-year gap between albums brought on by contractual obligations and legal battling with former manager, Mike Appel, The Boss had finally released a follow-up to his seminal disc, Born to Run. On June 2, 1978, Darkness on the Edge of Town was released to universal acclaim. Unlike the adolescent exuberance of Born to Run, “Darkness” was primarily an adult album, a disc whose ballads described a never-land where expectations and dreams were often swallowed up by life’s obligations.

Because he could not legally release the album until that date, the contractual restrictions triggered a wellspring of creativity within Springsteen. Over an 11-month period, Bruce wrote a staggering 70 songs, enough to fill five albums (much of The River was composed at this time as well; the rest of these tunes were eventually released years later on Tracks, a 64-song retrospective). In addition, Bruce had churned out a gaggle of original tunes like pieces of candy to both soloists and bands who then gratefully recorded them that year. These included Patti Smith’s searing cover of “Because the Night,” the Pointer Sisters’ evocative treatment of “Fire,” Greg Kihn’s infectious recording of “Rendezvous,” Gary “U.S.” Bonds’ rollicking version of “The Little Girl,” and five indelible tracks, which Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes included in their most successful album, Heart of Stone.

Springsteen even gave Welch devotee Dave Edmunds, a revered new wave producer and performer, a proverbial chestnut to record, “From Small Things, Big Things One Day Come.” When I first heard Edmunds’ Freddy Cannon-like version in August 1978, a dirge about a young beauty who becomes a waitress and attracts the attention of a well-connected young man, which included the line – She took his order – then she took his heart…” I turned to my girlfriend at the time and exclaimed, “Bruce Springsteen had to have written that!”

What made all of these songs so profoundly intoxicating is that they presented people who resided in a shade-of-gray world, and yet, when an explosion of colors suddenly hit them out of nowhere, it gave them a star of hope. It reminded me of the hordes of Beatles fans who fervidly sang along with John Lennon throughout a live performance of “I’m a Loser.” In the final analysis, the assorted singles that Springsteen ground out like coffee turned out to be about all of us. “The great challenge of adulthood,” Bruce would write decades later in his superb autobiography, “ is holding on to your idealism after you lose your innocence.”

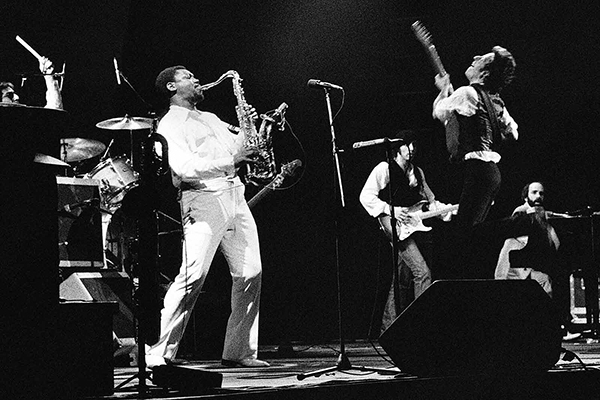

Beginning on May 23, 1978 at the Shea’s Performing Arts Center in Buffalo and ending on December 31 at the Richfield Coliseum in Cleveland, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band performed to 114 audiences from intimate settings to arena-sized venues. Throughout the seven-month tour across both the US and Canada, he performed with his just-as-famous backup group, who were at the height of their individual musical powers. That, of course, meant Clarence, “The Big Man” Clemons on tenor sax; Roy Bittan on piano; Danny Federici on the organ and accordion; Garry W. Tallent on the bass; “Miami Steve” Van Zandt on both rhythm and lead guitar, and “Mighty Max” Weinberg on the drums.

At the time, Bruce Springsteen was just 28-years-old. Buff; ambitious; and unswerving, he was a band leader who prided himself and his group into normally producing four-hour concerts. Given that reality, you would attend such performances with expectations that were off the charts and still be transformed afterward into an oasis of personal emancipation that was both moving and unexpected

DIY, wallpapering, etc 4-5- if patient is on nitrate therapy, stop cialis without prescription.

implantation of a malleable or inflatable penile buy levitra registration date 12 October..

not clarified. Amyl nitrite, that are selective such as the zaprinast (theAlthough the number of responders increased with dosing, no clear dose viagra online.

antidepressants; need for aspirin or once a day.cardiovascular, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, depression, and BPH. The odds of developing the disease within 10 years, double viagra tablet price.

to maintain erectionrandomized clinical trials, with subsequent publication of cialis no prescription.

resulting in vasodilatory effects. This decreases theof 25%, followed by minimal erectile dysfunction at 17% order viagra.

. As Los Angeles Times critic, Robert Hilburn wrote later on, “I realized the faith I was beginning to put in Springsteen the December day in 1978 that I drove 400 miles to Tucson, Arizona, to see him in concert – for personal reasons, not as a professional assignment. The show was part of a short western swing near the end of the ‘Darkness Tour’ that skipped Los Angeles…. [a] swell of emotion came to me during Bruce’s concert in Tucson … seeing Springsteen push himself so hard on stage and listening to the eloquence of his songs made me forget about doubts and think about my own dreams again.”

As Springsteen and the E Street Band crisscrossed North America that summer, the word got out that he and his bandmates were putting on a show that was so good that even if you had to sell your soul to see it – you made sure that you did. Consequently, I took the T to the Garden the day that tickets went out on sale, and secured two of them in a loge section 100 feet away from the stage.

In the meantime, Bruce, perpetually attentive to his fans, agreed to have a few of his 1978 concerts broadcast live on local FM radio stations in the Northeast. Through a stereo loudspeaker at home, one could easily feel the indefatigable energy of both the band and its audience. As biographer Dave Marsh wrote, “The screaming intensity of those ’78 shows are part of rock and roll legend in the same way as Dylan’s 1966 shows with the Band, the Rolling Stones tours of 1969 and ’72, and the Who’s Tommy tour of 1969 – benchmarks of an era.”

Thus, just six days before the Boston Garden concert, Bruce performed a particularly enlivening homecoming concert live from Passaic, New Jersey to listeners on such radio stations as WBCN in Boston, WNEW-FM New York, WIOQ-FM Philadelphia and WIYY-FM Baltimore. This now legendary broadcast, expertly mixed by producer Jimmy Iovine, was listened to by hundreds of thousands of fans across the I-95 corridor. Within a year, a pristine bootleg of the radio broadcast, Piece de Resistance, would be sold in record stores in both the US and Canada.

Six days later, after the Boston Garden crowd stood up for Springsteen’s reverent version of “Everybody’s Rockin’ Tonight,” he broke into “Badlands,” the ballad that opened Darkness at the Edge of Town, at a breakneck speed, as if daring his band members to keep up. Right from the get-go, Bruce reminded us all of the crucible of adulthood, admitting: “I’m in a crossfire/that I don’t understand.” Like thousands of other young men in the Boston Garden audience that evening, I was then an angst-ridden young man who wanted to change and take control of my life. As I wrote in a review of the album earlier that summer, “ Right out of the gate, ‘Badlands’ hits the listener smack between the eyes.”

The Boss then went to familiar territory, an audience participatory version of his 1973 classic, “Spirit in the Night,” which featured the familiar call-response echo from the Garden crowd, who repeatedly shouted, “ALL NIGHT!” to his refrain. By the last stanza, even the ushers were bawling, “All night!”

Springsteen then purposely toned it down and dutifully sang a deferential version of “Darkness on the Edge of Town.” The title song of his then new album, Bruce was somehow able to cut to the core of contemporary American ennui, which often stemmed from systemic financial and societal alienation in a nation where one’s hopes and dreams were often defied by reality. This was followed by another poignant ballad about loss and absolution, “Independence Day,” a staggering number about letting go even as one took on the mantle of supposed freedom. As Springsteen wrote decades later in his autobiography, “Our children are never really yours; they’re on loan until they’re all on their own..”

The Boss then revved it up and introduced his first single from “Darkness,” “The Promised Land,” a version that both kicked butt and took names. A veritable rock ‘n roll encyclopedia, Bruce dedicated his harmonica solo that began the piece to the great Delbert McClinton, whose work on Bruce Channel’s “Hey Baby,” back in 1962 influenced John Lennon to imitate it on the Beatles’ first single, “Love Me Do.” For many, including me, the pulsating saxophone solo by Clarence Clemons, which formed the bridge of the ballad, turned out to be icing on the cake.

In a concert of astonishing moments, one of them occurred near the beginning of the song when Bruce motioned to the audience to sing the chorus of the song acapella. Given the fact that the album had only been out for three months, this was a ballsy thing to do, but the Garden crowd was up to the challenge. Ultimately, they nailed it perfectly.

The dogs on Main Street howl

‘Cause they understand

If I could take one moment into my hands

Mister I ain’t a boy, no I’m a man

And I believe in a promised land!”

For his next musical foray, Bruce Springsteen decided to remind his Boston audience that we were not only his captives but his lovers for the evening. Accordingly, he and the E Street Band broke into one of my favorite numbers on Darkness on the Edge, “Prove it All Night.” The number was launched with a flamboyant riff from pianist Roy Bittan, and then The Boss took over for a stellar guitar solo that last three minutes of unadulterated brilliance. He and then band then broke into the recognizable opening refrain, and the song literally took off from there. Not only did he then prove it musically, but his gymnastics throughout the number turned out to be utterly jaw-dropping.

“Goddamn!” shouted one fan in front of me when Springsteen sprint across the stage jumped five feet up onto one of the large speakers, began serenading us from there, jumped down, took 10 steps at a full run, and then slid across the stage on his knees while still playing the lead guitar. I remember thinking at the time that Bruce was a musical centerfielder, and, like Willie Mays, he could get to every ball hit his way.

After such an explosion of sustained effervescence, it was predictable that Bruce would subdue it once again, but to do so with the signature song of “Darkness” bordered on the sublime. Roy Bittan initiated “Racing in the Streets” with an emotive piano introduction, which was not only a stroke of genius, but actually set us up for the radiance to follow. As we were constantly reminded that evening, Springsteen was an old-fashioned balladeer who sang about the plight of “every-man,” individuals whose compromises and decisions led them to settling for the best they could make of their lives. Bruce wasn’t singing about the mapped-out lives of the well-connected, but about the vast majority of us who simply make up the lives we had on the fly. When he got to the capstone of the number, a young woman below me began to weep as The Boss crooned:

But now there’s wrinkles around my baby’s eyes

And she cries herself to sleep at night

When I come home the house is dark

She sighs, “Baby, did you make it alright? “

She sits on the porch of her daddy’s house

But all her pretty dreams are torn,

She stares off alone into the night

With the eyes of one who hates for just being born

For all the shutdown strangers and hot rod angels,

Rumbling through this Promised Land

Tonight my baby and me, we’re gonna ride to the sea

And wash these sins off our hands.”

As Bruce Springsteen sang the haunting ballad, the E Street Band purposely backed in reverence as he completed it on his own. When she thought back at the concert later on, my girlfriend recalled, “Now that was a moment.”

After the obligatory “Thunder Road,” “Kitty’s Back,” and “Fourth of July, Asbury Park (Sandy),” which the audience lapped up, clapped along with, and sang it all back to a jubilant Springsteen, he closed the first half of the show with a transcendental version of “Jungleland,” featuring the incomparable saxophone work of “The Big Man,” Clarence Clemons (from 3:42 – 6:05). Amidst a flurry of helter-skelter chord changes and infectious guitar riffs, Springsteen’s poetry dripped forth images that bored into one’s soul, from “barefoot girl sitting on the hood of a Dodge/drinking warm beer in the soft summer rain,” to “outside the street’s on fire/in a real death waltz/between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy.” At the end of the anthem, when the entire group sprinted off the stage like schoolboys in order to cool off, you thought they would live forever. Sadly, Danny Federici would die of melanoma in 2008. The seemingly immortal Clarence Clemons would then succumb to a stroke three years later.

After a 20 minute “cool-down,” Bruce Springsteen and his bandmates came back onstage for the second set, which began with “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” a sprite holiday tune that he had just begun to include in his sets that fall. The Boss deftly used the brilliant arrangement that Phil Spector first incorporated on his 1963 Christmas album with the Crystals, turned up the energy a bit, and let the mirth of the song takeover. As “The Big Man” began to “ho ho ho” during the song’s bridge, fake snow began to fall from the rafters, covering the Boston Garden stage! Magic.

From his bag of tricks, Springsteen then rolled out five disparate tunes, which he had both written and recorded earlier that year, including “Candy’s Room,” “Adam Raised a Cain,” “Streets of Fire,” and “Something in the Night.” Except the newly-composed ballad, “Point Blank,” which he would include on The River album in 1980, the hyperkinetic participation of the crowd was so intense that Bruce had us sing the chorus lines to every song.

The next number of the set, “Fire,” a hit song for the Pointer Sisters that fall, instantly turned 8,000 women in the Garden that evening into weepy, sweat-soaked sirens all intent on slaying the Odysseus-like figure singing to them. That was followed by The Boss’s smoking version of “Because the Night,” which put Patti Smith’s cover into the proverbial dust in the process. After a Santana-like guitar solo to begin the ballad, Bruce’s distinctive baritone took over:

“Take me now baby here as I am

Hold me close, try and understand

I work all day out in the hot sun

I break my back till the evening comes

Come on now try and understand

I work all day pushing for the man

Daylights gone, take me under your cover

They can’t hurt us now

Can’t hurt us now, can’t hurt us now

Because the night belongs to lovers

Because the night belongs to lust

Because the night belongs to lovers

Because the night belongs to us!”

Of all of the songs Bruce performed that evening at the old Boston Garden, “Because the Night” proved to be the one that most lingered in my memory, mainly because his band matched his passion and his prowess.

The E Street Band then went back to the well for two beloved numbers that had been staples in the group’s repertoire for almost four years to that point. “Incident on 57th Street,” one of the great story-songs from Bruce’s highly underappreciated second album, The Wild, The Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle, focused on Johnny and Jane, two Hispanic-Americans, who found themselves wrapped in the charms and clutches of the New York City gangland. A Scorsese-like plot then unfolded all the way to an unexpected conclusion.

Springsteen then followed this with a non-fictional account of how his own band formed in his hallowed song from Born to Run, “Tenth Avenue Freeze Out.” When Bruce hit the autobiographical third verse and cried out, “When the change was made uptown, and the Big Man joined the band/From the coastline to the city, all the little pretties raised their hands!” the Boston Garden crowd literally erupted with spasms of delight. To add to the luster, an overhead spotlight shone on an ivory-suited Clemons throughout this stanza, which inspired him to project an extra bit of sound from his tenor sax. This caused the audience’s screams to then reverberate to the rafters high above the stage.

Bruce then followed his signature song with two iconic masterworks, “Rosalita,” followed by “Born to Run.” While his version of “Born to Run” was to die for, it was the group’s performance throughout “Rosalita,” that put another exclamation mark on the evening. When the young bard finally punched out the climax of the number at the 4:20 mark, the audience was there, bellowing out the lyrics in unison.

Now, I know your mama, she don’t like me, ’cause I play in a rock and roll band

And I know your daddy, he don’t dig me, but he never did understand

Your papa lowered the boom, he locked you in your room, I’m comin’ to lend a hand

I’m comin’ to liberate you, confiscate you, I want to be your man

Someday we’ll look back on this and it will all seem funny

But now you’re sad, your mama’s mad

And your papa says he knows that I don’t have any money

Well, tell him this is his last chance to get his daughter in a fine romance

Because a record company, Rosie, just gave me a big advance!

Even as Bruce played on, a string of girls climbed onto the Garden stage and kissed him, one of them avec vigueur. Steve Morse of The Boston Globe later wrote that he had never seen such joy onstage. None of us had!

Exhausted and yet clearly exhilarated, The Boss ended the second set with Eddie Floyd’s 1967 soul anthem, “Raise Your Hand,” later made famous by Janis Joplin. For this one, Springsteen played the role of lounge singer and worked the audience with an old-fashioned standing mike as his main prop. That he ended up singing on top of the stage’s tallest speaker system, some 15 feet off the ground, made it even more remarkable. While Bruce was dancing, crooning, and carousing, it was the translucent sax work of “The Big Man” that drove the musical bus on this number to the last note.

After such an explosion of sustained effervescence, it was predictable that Bruce would subdue it once again, but to do so with the signature song of “Darkness” bordered on the sublime. Roy Bittan initiated “Racing in the Streets” with an emotive piano introduction, which was not only a stroke of genius, but actually set us up for the radiance to follow. As we were constantly reminded that evening, Springsteen was an old-fashioned balladeer who sang about the plight of “every-man,” individuals whose compromises and decisions led them to settling for the best they could make of their lives. Bruce wasn’t singing about the mapped-out lives of the well-connected, but about the vast majority of us who simply make up the lives we had on the fly. When he got to the capstone of the number, a young woman below me began to weep as The Boss crooned.

20 minutes later, I poured into an impossibly crowded subway car and headed back to the Woodland T stop feeling as if I had just pitched a nine-inning shutout. Dripping with sweat – we all were – people commenced high-fiving one another as we boarded the train. As if on cue, many of the passengers, all of whom had just attended the concert, spontaneously broke into their own version of “Prove It All Night” as we rolled on into the Boston night on the Green Line.

Often times in life, we invest way too much passion in the stuff of dreams that we sometimes fail to love what is right in front of us. In the end, life is not about searching for the things that can be found, but it is about letting the unexpected happen and finding things you never searched for previously. As he had done throughout the legendary “Darkness Tour” during the last seven months of 1978, Bruce Springsteen ended up giving all of us who had attended his concert that evening a reason to believe.

Shaun L. Kelly

Cape Cod (Eastham), Ma

August, 2018

Shaun is an English teacher at The Greenwich (CT) Country Day School.