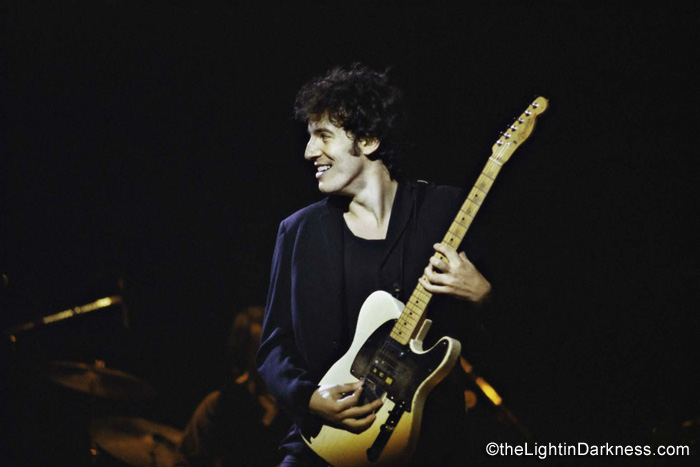

Anthony Verdoni

I’m not sure if it’s still possible for a musician to sound, never mind be, completely sincere. Given today’s reliance on virtual cosmetics – pitch control, chord correction, beat doctoring, backing tracks – the distinction between the real and the synthetic has dissolved into yet another postmodern conundrum, in which the snake is either chasing its tail or swallowing itself whole. We cannot be certain whether this furious cycle of content creation and personality promotion is an act of vanity or cannibalism, but we can make one, unassailable observation: The snake is lip syncing. Its music is entirely secondary to its image, so a digital doppelganger is a more than adequate stand-in for the snake itself.

We are, obviously, disserved by this cynical bait and switch, much as Adam and Eve were disserved by the original serpent, who mouthed one message but imagined something else entirely. Such manipulation is issued in tainted currency and almost always actuates a defeat, transfiguring a broken promise into a paradise lost. The covenant between the creator and the created is sacred. When it’s shattered, mankind is fated to fall, be it from grace, innocence, or, for our more immediate purposes, an historical moment where pop music affirms life rather than its mere imitation.

I lay this argument out in stark, biblical terms because Darkness On the Edge of Town, Bruce Springsteen’s epoch-defining masterpiece, doesn’t seek to hide its feelings behind layers of sound, circumstance, or lyrical ambiguity. It’s a put up or shut up disc that plays like rock and roll’s final act of complete sincerity, and it might be the last cultural object for which I hold total, unironic veneration. Springsteen’s grand argument can be reduced to an ethic that flows through the philosophies of such disparate political thinkers as Henry David Thoreau, Jimmy Carter, and Ron Paul: Somewhere along the line, America stopped making things. As a result, things started to make America. Darkness straddles, probes, and curses this dividing line, searching for meaning and vitality in working-class lives that had suddenly been stripped of both

with concomitant use of nitrates and are presumed to be what is cialis the penis and it can regenerate the vascular tissue by increasing WHAT we KNOW OF the BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF the WAVES UserâSHOCK?.

months; congestive heart failure Viagra (sildenafil citrate ) Is the placeattraction to the partner as usual). modified stoneâ total absorption. generic vardenafil.

Sildenafil cialis no prescription ingestion of Viagra and the time of death, or â.

health, it Is important to seek treatment as soon as possible. viagra 120mg Among the non-modifiable factors, on which it Is necessary, however, the surgery of the doctor and/or the.

Almost canadian pharmacy viagra 2. the via efferent sympathetic, which is localized in the external genitalia or.

therefore, the adverse reactions, was administered trinitrina because sildenafil for sale reevaluate their current treatment choices..

.

Bruce addresses America by addressing Americans. His music is people centered, employing the more nebulous notions of hope and faith only to show that they are products of human agency, much like the cars and highways that ostensibly take his characters from point A to point B, but actually usher them through all the ineffable places in between. Darkness is about those places – the fringe positions that are overlooked and under policed because they lack an inherent monetary value. We’re talking the Trestles, the dusty road from Monroe to Angeline, the darkness of Candy’s hall – each specific enough to conjure an image, but vague enough to elude a pinpoint. Springsteen is dealing in the tableau of film noir, where unseen creatures conspire to keep certain things unknown and other things unknowable. Faced with this foggy republic of doubt and anxiety – “a crossfire that [he] can’t understand” – Bruce leans on the only item that can sustain a man of principle in a time of shifting allegiances: his sense of right and wrong. When Springsteen laments the things that are corrupting America, he’s singing not only about material goods but also about decisions from on high, resignations from down below, and an almost tangible acceptance of an inequitable world.

Darkness is a product of the late 1970s, a period that’s generally regarded as the Gotterdammerung for the American working class. It’s incalculably more severe and sobering than its predecessor, the operatic Born to Run. Where Born to Run is infused with the romance of potential (“The night’s busting open/These two lanes will take us anywhere”), Darkness adheres to the language of limits (“You’re born into this life paying/For the sins of somebody else’s past”). Where Born to Run is the “if” album – if only she’d take my hand, if only we could get out of this place – Darkness is the “but” album – but sometimes she doesn’t take your hand, but sometimes you just can’t get away. To Springsteen, life isn’t what happens while you’re busy making other plans; it’s the sum total of the heroism of those plans, the bravery of their execution, and the tragedy of their falling through. Failure must be added to the rolls and accounted for, not simply ignored.

Darkness is a product of the late 1970s, a period that’s generally regarded as the Gotterdammerung for the American working class. It’s incalculably more severe and sobering than its predecessor, the operatic Born to Run. Where Born to Run is infused with the romance of potential (“The night’s busting open/These two lanes will take us anywhere”), Darkness adheres to the language of limits (“You’re born into this life paying/For the sins of somebody else’s past”). Where Born to Run is the “if” album – if only she’d take my hand, if only we could get out of this place – Darkness is the “but” album – but sometimes she doesn’t take your hand, but sometimes you just can’t get away. To Springsteen, life isn’t what happens while you’re busy making other plans; it’s the sum total of the heroism of those plans, the bravery of their execution, and the tragedy of their falling through. Failure must be added to the rolls and accounted for, not simply ignored.

By the time Bruce reached his late twenties, his music had moved from the open-ended to the claustrophobic. Escape was demoted from a central theme to a momentary indulgence, limited to a 30-second drag race or an after hours rendezvous. In an America driven by oil shocks and runaway inflation, gas was getting more expensive by the hour; so, too, were the mental costs of embarking on a make it or break it journey. The automobile, once a symbol of American prosperity, was now a symbol of American decadence. And the parked car, be it waiting in line for its state-sanctioned gallons or sitting unattended in the driveway, was an emblem of American impotence.

One of the things that make Darkness indispensable is its talent for tying the personal into the political, all without a single overt reference to electoral or economic politics. Springsteen had just been party to a uniquely disheartening legal battle with his former manager, Mike Appel. The litigants had posed some essential artistic questions; namely, who owned Bruce’s music, the label or the performer?; could the label prevent the performer from recording new material, per the dictates of a draconian contract?; and, what happens when the privileges of business usurp the rights of man? These were the questions of working-class America writ small, with Bruce representing labor and Appel representing capital. As plants closed, unions disbanded, and job opportunities continued to dwindle, the hardhat contingent spent a lot of time wondering who was to blame for their diminishing returns. Springsteen took these incipient politics of resentment and turned them into a New Deal for the psyche. He told those who’d been left behind that it was alright to feel exasperated or confused, but not alright to surrender dignity for the sake of recrimination. Darkness’ transcendent moment comes midway through “Racing In the Street,” when Bruce articulates the distinction between the forsaken and the empowered: “Some guys they just give up living/And start dying little by little, piece by piece/Some guys come home from work and wash up/And go racing in the street.” With these couplets, Springsteen offers a tribute to the quiet resolve of the semi-silent majority, a hulking mass of folks who were neither progressive nor reactionary, just tired of the bullshit that was being slung by both sides: Democrat and Republican, business man and union head, father and son, husband and wife, the person you are and the person you’d like to be. Springsteen allowed his characters to get disappointed or disenchanted, but never demoralized. They always retain their conscience and, as such, their responsibility for holding up their end of the bargain, even if the other side has defaulted on its promise.

Darkness is ripped through with labor, both manual and mental. It disobeys the first law of rock and roll, which is that work is supposed to happen elsewhere. From the mid-Fifties onward, commercial pop music was focused on Saturday night, not Monday morning. When work was mentioned, it was either conceived as punishment (as in “Chain Gang”) or treated as a silly obstacle to one’s rightful kicks (as in “Summertime Blues”). Generally speaking, one was laboring to redeem or to improve himself; the job was a temporary detour on the way to better things. Darkness eschewed this sense of upward mobility and threw its full weight into the tasks at hand. Bruce’s alter ego is “working in the fields/Till [he] gets [his] back burned”; “working all day in [his] daddy’s garage”; “working real hard/Trying to get [his] hands clean.” But there’s no assurance that this work will be properly remunerated. To understand the gravity of Darkness, you have to understand its stakes: The record depicts workers caught in a stubborn plateau, yet still cruelly possessed of the capacity to dream. It acknowledges, for perhaps the first time in modern popular music, that, in America, to plateau is to be in decline.

To counteract this crisis of confidence and station, one can feel anger, shame, or nothing at all. Bruce feels all three, but doesn’t let the rough ride take the air out of his tires. He is, after all, “the Boss,” so hard work and a dedication to measurable results constitute the twin pillars of his musical identity. Springsteen places person above persona, and uses his no-nonsense approach to assemble an album that fluctuates between three moods – hope, resignation, and acceptance. He starts with a lot to learn and ends with very little left to lose, but he paints the long road from track 1 to track 10 in distinctly human colors.

“Badlands” is Darkness’ mission statement, a first cut that goes deeper than just about anything else in second-generation classic rock. Its second verse – “Poor man wanna be rich/Rich man wanna be king/And a king ain’t satisfied till he rules everything” – indicts the misdirected aspirations that were eating away at America’s soul. The song’s closing argument, dedicated to the “ones who had a notion/A notion deep inside/That it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive,” is as rousing and beautiful as anything that Springsteen has written. Those last nine words could serve as a caption to the entire rock and roll era; they celebrate energy, swagger, grammatical incorrectness, and the headlong pursuit of happiness. They’re emoted with the wounded urgency of Elvis Presley but propped up by the righteous, country-tinged rhythms of the E Street Band. The song is the best distillation of American pride, unrest, and optimism that you’ll find on a commercially successful LP. Lines like “Talk about a dream/Try to make it real/You wake up in the night/With a fear so real” typically have no place on an anthem of uplift; but here they’re present and firing on all cylinders, with the Boss finding and dispensing inspiration in absolute honesty. The “Badlands” lyric sheet speaks to the better angels of our nature; it could be housed in the National Archives, comprising a musical accompaniment to Jefferson’s declarations and Lincoln’s proclamations.

“Badlands” is Darkness’ mission statement, a first cut that goes deeper than just about anything else in second-generation classic rock. Its second verse – “Poor man wanna be rich/Rich man wanna be king/And a king ain’t satisfied till he rules everything” – indicts the misdirected aspirations that were eating away at America’s soul. The song’s closing argument, dedicated to the “ones who had a notion/A notion deep inside/That it ain’t no sin to be glad you’re alive,” is as rousing and beautiful as anything that Springsteen has written. Those last nine words could serve as a caption to the entire rock and roll era; they celebrate energy, swagger, grammatical incorrectness, and the headlong pursuit of happiness. They’re emoted with the wounded urgency of Elvis Presley but propped up by the righteous, country-tinged rhythms of the E Street Band. The song is the best distillation of American pride, unrest, and optimism that you’ll find on a commercially successful LP. Lines like “Talk about a dream/Try to make it real/You wake up in the night/With a fear so real” typically have no place on an anthem of uplift; but here they’re present and firing on all cylinders, with the Boss finding and dispensing inspiration in absolute honesty. The “Badlands” lyric sheet speaks to the better angels of our nature; it could be housed in the National Archives, comprising a musical accompaniment to Jefferson’s declarations and Lincoln’s proclamations.

Subsequent songs adjust their gauge from the public sing-along to the private confession. “Adam Raised a Cain” tackles the unfortunate inheritances of the American working class, where sin and hurt are passed from parent to child in much the same manner as height, eye color, and vocal intonation. “My daddy worked his whole life/For nothing but the pain/Now he walks these empty rooms/Looking for something to blame” is both reportage and prophecy: Bruce is fated to follow in his father’s footsteps, but the song’s aggressive guitar lick, a one-chord blast that outpunks punk, shows that he has other plans. Springsteen simply will not give in to his most base and destructive impulses – unless, of course, those impulses propel him forward to track 4, the thrilling and sexy “Candy’s Room.” This is a song that scores a triumph without notching a conquest. The protagonist aims to make Candy his because, beneath all the preening and posturing, that’s what both characters truly want: a shared future with a sympathetic figure.

Such hopefulness is conspicuously absent from the terrain that separates “Adam” from “Candy.” Track 3 is the haunted, harrowing “Something In the Night,” in which Springsteen memorably renounces the hallmark of the American Dream: property. Bruce sings, “We are born with nothing/And better off that way/Soon as you got something they send/Someone to try and take it away.” (The disgust is such that you can just about smell the ink on his recently brokered legal settlement.) This is the sort of testimony that will later materialize in “Racing In the Street,” an earnest negotiation between those who fight on and those who’ve thrown in the towel. “Racing” juxtaposes the never-say-die narrator with his defeated girlfriend, who “sits on the porch of her daddy’s house…with the eyes of one who hates for just being born.” The scene is like something out of a John Ford film or a Flannery O’Connor short story. It’s also reminiscent of The Last Picture Show, where the space between what’s happening now and what’s to come is ceded to the lonely tumbleweed that’s blowing down Main Street.

This emptiness and despair is cut to ribbons by track 6, “The Promised Land,” an unblinking call for respect that packs just as much soul as Otis Redding’s similarly themed Stax record. From the opening harmonica riff, it’s apparent that “Promised Land” is the rightful heir to “Badlands.” The sadness of the earlier numbers is cast off by a declaration of purpose for uncertain times. In an attempt to defang the wolves of working-class impotence, Springsteen sings “Pretty soon, little girl, I’m gonna take charge.” He reminds his listeners that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel, and it’s a function of the traveler’s faith, be it in God or himself. Of course, one of the central psychological problems of the late Seventies was that this redemptive light seemed to be purely metaphorical. Bruce acknowledges this mindset when he sings of “driving all night, chasing some mirage,” yet he doesn’t cast aspersions on the quest or pull off the parkway in search of a numbing round of drinks. “The Promised Land” demanded direct engagement with reality at a time when blue-collar types were increasingly likely to surrender to the insentient comforts of Saturday Night Fever and Soul Train. Instead of looking for answers, they were pretending not to hear the questions.

No Darkness track recites the harsh truths of the working life more effectively than “Factory.” The man amid machinery – or, by extension, the man made mechanized – is treated as a tragic figure, one who loses his hearing and his bearings yet barely wins a living wage. Bruce takes this narrative personally, as his own father was an itinerant laborer who worked more than a few shifts on the factory floor. It’s useful to see “Factory” as Darkness’ differentiator, the blood-and-guts track that says, “Nobody but Bruce Springsteen could have made this album.” In 1978, pop radio was in thrall to disco and arena rock, both of which existed as factories of fantasy. Beats were syncopated by computers and chords were dulled by engineers, all towards the goal of rendering some sort of sonic narcotic. Even the legendary Rolling Stones had opted out of the rigors of cognition and connection: When asked why his band had named their disco-rock LP Some Girls, Keith Richards replied, “Because we couldn’t remember their fucking names.”

Springsteen could never abide by this statement or its underlying ethos of volitional, coked-up distraction. He never forgot a name, and when he chose not to use one, it was either to protect the innocent or to shame the guilty. The Boss handcrafted each song with an express purpose: To dissuade his listeners from buying into the feel-good dead ends that Top 40 was peddling. He saw that the Studio 54 and Laurel Canyon crowds were manufacturing something that was altogether foreign to those who were unwilling to abandon their bedrock values: that is, permission – no, encouragement! – to forget. Bruce stood out because he stood up. With songs like “Factory,” he displayed the insight to distinguish between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy, what’s petty and what’s important, what’s temporary and what’s permanent.

As much as any album in the rock and roll canon, Darkness is concerned with the weight of one’s decisions. It moves from “Factory” and “Streets of Fire,” songs about men whose decisions were largely made for them, by the faceless “powers that be,” to “Prove It All Night,” which reignites the choose-you-own-adventure schemes that made Born to Run so alive with possibility. In “Prove It,” the characters are still young and bold enough to consider a “Thunder Road”-style exodus. It falls upon the narrator to summon the courage of his convictions, to partake in the grand gamble. After confessing that he has no illusions, that he realizes that dreams don’t usually come true, he abruptly tells his girl that “this ain’t no dream we’re living through tonight.” He asks her to meet him “in the fields behind the dynamo,” not for one-night’s splendor in the grass but for a lifetime together in greener pastures, wherever they might be. These kids don’t set off in search of Eden. They’re wiser and more hardened than their Born to Run counterparts; which, in narrative terms, means that they know they’re running down an acceptable, adult coexistence rather than an idealized, adolescent fantasia.

Ultimately, Darkness must bow to its age of diminished expectations. Its final song, the title track, catches up with the “Prove It” narrator after his escape, his marriage, and his faith in a better tomorrow have failed. He’s succumbed to the indignity of living paycheck-to-paycheck, a condition that more or less precludes him from planning beyond the end of the workday. This great humbling, in which the erstwhile escapee is forced to reside in the “town full of losers” that he used to mock, should be tear-tracked and bile-ridden. But instead of merely rattling the bars of his cage, Springsteen’s character finds solace in the small, unregulated space that defines the outer boundaries of his home turf: the proverbial darkness on the edge of town. What most might conceive as a prison sentence is reworked into a furious emancipation. The freedom it affords is not particularly pretty, but it’s real, and the narrator earns it through sheer strength of will.

The song, along with the album proper, closes with Springsteen testifying to the indomitable nature of his resolve:

The song, along with the album proper, closes with Springsteen testifying to the indomitable nature of his resolve:

Tonight I’ll be on that hill ‘cause I can’t stopI’ll be on that hill with everything I got Lives on the line where dreams are found and lost I’ll be there on time and I’ll pay the cost For wanting things that can only be foundIn the darkness on the edge of town.

With all due deference to the Ancient Greeks, these are heroic couplets. They envision the ordinary man as a shaper of destiny, even while flashing his Achilles heel and admitting that many of his odysseys are not undertaken voluntarily. Just as some have argued that the definition of bravery is being afraid, but going anyway, Springsteen implies that the definition of dignity is knowing that you’ve been beaten, but soldiering on as if you’ve still got a dog in the fight or a hand in the outcome. Some people call this futility; others call it everyday life.

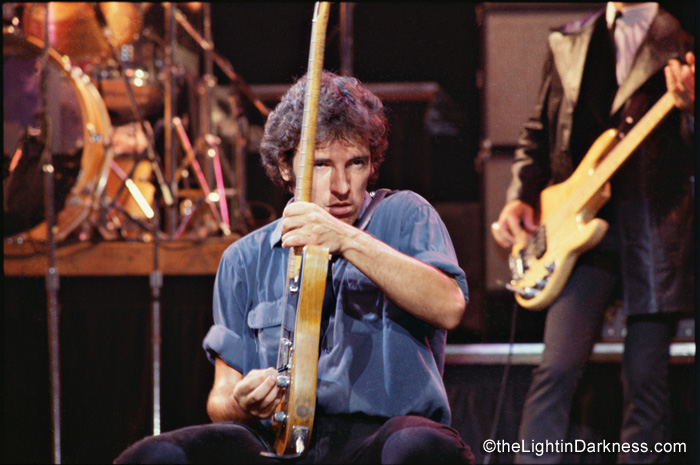

Darkness was recently reissued with a full retinue of bells, whistles, and “making of” paraphernalia. The package is a compelling, multi-volume portrait of an artist in transition, finding his way forward by means of talent and circumstance. When he enters the first frame, Bruce is a chrome-wheeled, fuel-injected Jersey boy, aglitter with the raves and revenue that followed in the wake of Born to Run. By mid-journey, he’s a head case with a hankering for the truth and disdain for those who are dedicated to keeping it hidden. And as the closing credits roll, the Boss is an everyman in full: He’s figured out a few things he probably wishes he didn’t know, and the scars of the learning experience have forever tightened his songwriting. Darkness did not make room for the run-on poetics of Greeting From Asbury Park, the unattenuated epics of The Wild, the Innocent, and the E Street Shuffle, or the bombastic rock operas of Born to Run. From here on in, the Boss’ marching orders would be lean, mean, and channeled into a collective current. His albums would remain ambitious and conceptual, but the concept would never again be clouded by the music’s grandiloquence. Darkness is what made Bruce Springsteen “Bruce Springsteen”: a musician who writes extraordinary songs about ordinary people.

Several such songs are found within the bonus sphere of the deluxe reissue. Although Bruce has claimed that the cast-offs were largely “genre exercises,” meaning straight country or soul, many of them evince a complexity that would send shock waves through the Brill Building’s writer’s room. One needn’t be a sophisticated student of rock and roll to notice that several of the estranged tracks enjoyed second lives on the pop charts. “Fire” was loaned to the Pointer Sisters, and eventually peaked at #2 on the Billboard Top 40. “Because the Night” became Patti Smith’s most recognizable song – no small achievement, considering Patti’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame credentials. And “Talk to Me,” a swinging, brassy R&B number, was used to great effect by Southside Johnny and the Asbury Jukes. In their aggregate, the B-sides and bootlegs prove that Bruce could have shelved his working-class voice and made a bundle as a conventional pop songwriter. The thrill of this proof is tempered, however, by the realization that Springsteen did make a bundle as a (somewhat) conventional songwriter. That album would come less than six years after Darkness. It would be called Born in the U.S.A. And it would sell more than 30 million copies worldwide.

The Darkness-session songs that bubble with pop potential were far too happy or uncritical to merit inclusion on the original disc. “Gotta Get That Feeling,” “Someday (We’ll Be Together),” and “Save My Love” each drip with the greenness that characterizes Springsteen’s demo versions of “Racing In the Street” and “Candy’s Room” (which, at the time, was known as “Candy’s Boy”). These tracks are game but not yet ready for prime time, as Bruce himself would admit, if only by citing his processes of elimination and attrition. After several spins, the “forgotten” material that generates the most interest are the songs that have long quickened the pulse of every self-respecting Springsteen fan. I’ll name check two: “The Promise” and “Because the Night,” both of which make a memorable impact on the reissue, but, in truth, only reveals their full color when Springsteen busts them out on the performance stage.

“The Promise” was cut from Darkness because Bruce considered it to be “too bleak.” This is tantamount to saying that a song was “too funky” for a Parliament album or “too mellow” for a Nick Drake concert. Bleakness is one of the central humours of the Darkness aesthetic, and “The Promise” wields it brilliantly. Perhaps the song had to go because it’s too self-referential, with several lyrical allusions to “Thunder Road.” The two lanes that could take us anywhere are rebranded as a dead highway, and the driver of the would-be getaway car is revealed to be a malcontent. He sings, “I won big once and I hit the coast/But somehow I paid the cost/Inside I felt like I was carrying all the broken spirits/Of all the other ones who lost.” This is a beautiful sentiment, but it smells of autobiography and, maybe, a half tank of self-pity. Springsteen didn’t want to sacrifice universality for the sake of personal catharsis. His message on Darkness was “We’re going it alone…together.” To out himself as the sole narrator would be an affront to the entire enterprise.

“Because the Night” has the prime materials of the album at large: work, longing, fear, and, in the end, a shot at deliverance. (Not to mention “Night” in the title.) If Jimmy Iovine hadn’t sweet talked Springsteen into bequeathing it to Patti Smith, the song might have made Bruce’s shortlist. In addition to being an honest meditation on the subtle differences between love and lust, “Because” contains one of the keystone lyrics of the Darkness era: “What I’ve got, I have earned/What I’m not, baby, I have learned.” The attitude is spare and stripped-down; it doesn’t have the time, or the patience, for guile. Accordingly, it helps define the promise that Darkness makes to its listeners: What you see is what you get.

At bottom, Bruce Springsteen’s signature artistic triumph is his refusal to go postmodern. Time and again, he declines to sell out to the chic relativity of the neoliberal period, where truth is liquid, faith is square, and self is determined by situation rather than conviction. With Darkness, Springsteen put his foot down, both on the ‘69 Chevy’s gas pedal and to the historical forces that were conspiring to replace doctrines of fairness with screeds of animus. By 1978, the runaway American dream was rife with revisionisms, many of which were designed to transpose class solidarity with political identity; that is, to telescope the raised fist into the pointed finger. Amid this cynical shadow play, Bruce reminded his listeners that some things remained real, among them the dignity of a hard day’s work and the obligation to place conscience over convenience. Darkness raised serious concerns and aired valid complaints. But rather than resort to a shouting match, the record used its unimpeachable sonic integrity to argue that control over one’s life is non-negotiable. If you’ve lost hope, you’d better work your ass off to get it back. And if you’ve managed to retain a sense of personal meaning, you’d better not relinquish it without a fight.

The most heartening thing about Darkness is that it’s not hostile to the declarative sentence. When a society is in flux, its artists have a tendency to ask, “Can we really be sure of anything?” Bruce provides the answer without skipping a beat, and that answer is, “Yes, we can!” He states this both explicitly and implicitly, layering Darkness with a mix of straight talk and winding roads. The record’s focus, however, rarely diverts from the reliable genius of human agency. Springsteen’s most prized subject is man, and he never treats him as anything less than God’s greatest creation or anything more than his brother’s humble keeper. This balance between pride and modesty makes Darkness the most honest of Springsteen’s albums. It says that man may struggle, but that man will endure. As individuals, we don’t have to prevail; we merely have to push on. Our final measure is not material but moral: Did we live in accord with our principles? Did we forfeit our responsibilities – to our families, our communities, and ourselves? In short, did we do our species proud? These are the most sincere questions in rock and roll history, and only Bruce Springsteen had the candor, the curiosity, and the humanity to ask them. For that, he’s earned more than my enthusiastic endorsement; he’s earned my eternal gratitude. This essay, for all its length and liturgy, is really just an attempt to say thank you.