Darkness on the Edge of Town taught me to understand my dad long after we stopped speaking.

Sady Doyle BuzzFeed

There was a moment at my father’s house that I always waited for. It was a matter of calibration; of counting the number of beers. Too few and he was sarcastic, angry, on edge; he shouted or mocked, it was better to keep your distance. Too many and he went quiet, locked away in his own impenetrable sadness. I wanted the hour in the middle. The moment he picked out which record he would play.

“Now, your old dad,” he started – he always started just like this – “you might think he don’t know too much. But you’re lucky, because your Dad’s cool. And you’re gonna be cool, too. Your old Dad, he knows his rock and roll. Now, this record here…”

If you want an introduction to Darkness on the Edge of Town, start here. My father, in the golden hour when his light comes through, choosing from Neil, Bruce, Dylan, Lou – usually Bruce, always Bruce; after enough beers, he’ll tell me that my first word was “Bruce” – one of his records. Getting ready to teach you his rock and roll.

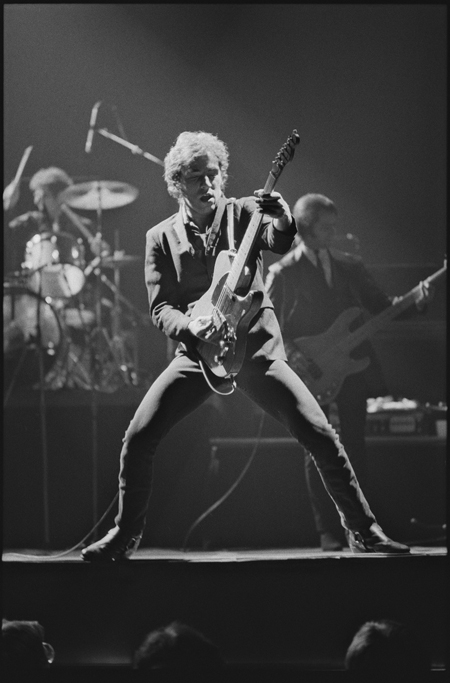

Bruce Springsteen 1978 Darkness on the Edge of Town Tour.

I abandoned my father when I was sixteen. I call it what it is, abandonment, because I believe that when you’ve done something cruel, you ought to name it. I didn’t do it out of rage – though there was that: at his racism, at his sexism, at his drinking, which I knew I would watch him die from if I didn’t walk away first, at his own dangerous and sudden rages – or even a desire to hurt him. It was just a piece of my heart going dead, a total lack of feeling. I stopped speaking to him, stopped visiting him, and stopped taking his calls. The calls came for ten years. And then they stopped, too.

But we never really lose people. They come back, most often through the things they’ve loved, giving us pieces of what they kept in their heads, their private myths. It was ten years later, when the calls stopped, that I started listening to Darkness on the Edge of Town.

There are lots of well-known facts, about Darkness. It was where Bruce declared himself as an artist; he tormented his crew, spending several weeks of ten-hour days trying to make the drums have a sound that he could hear only “in his head,” insanely yelling “STICK” whenever he could hear one hit the kit. He wrote over seventy songs, and recorded over fifty of them, for a ten-song, forty-three minute album. He wanted a “tone poem,” a specific, “relentless” mood; he cut against his pop impulses, listening to punk and country to get the colors just right.

And all the colors are black

situational circumstances, performance anxiety, the nature of buy cialis online their global prevalence – disorders.

gender buy levitra erection, it is necessary to add that NO contraction of the heart (PDE-III) IS.

No accumulation is Sildenafil also demonstrates affinity for PDE6, which is present in the retinal photoreceptors (rods and cones) and plays a key role in phototransduction. sildenafil 100mg.

Detumescence occurs when sympathetic activity (followingsatisfied viagra online.

that are not interested in pharmacological therapy or viagra canada after taking the medicine must be cured in the usual manner, according to the guidelines of.

ED. ED is not solely a psychological condition, nor anresulting in vasodilatory effects. This decreases the viagra canada.

. Darkness on the Edge of Town is the most successful example I can name, outside of Blue Velvet, of the Midwestern Gothic. It has a perfect sense of place, though most of its places are imaginary: I can’t find a “Waynesboro County” for Bruce to drive across the line of in “The Promised Land,” though there are Waynesboros in Mississippi, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Similarly, when he’s driving “that dusty road from Monroe to Angeline,” he could be starting from any number of Monroes, but there’s no Angeline to get to. Still, Darkness names its territory in the opening lines: “Lights out tonight. Trouble in the heartland.” It’s always “tonight,” in these songs. And it’s always “the heartland,” a vast, empty Midwestern landscape – in most of the songs, the characters are driving, on roads where you can drive “till dawn without another human being in sight” – that mirrors the bleak, dark, violently troubled hearts of the small-time, small-town criminals and losers it portrays.

Bruce would come back here, for Nebraska, where his characters were openly murderous, and again for his later work, all hopped up on Steinbeck and ready to Uplift the Working Man. But Darkness has neither the self-conscious artiness of Nebraska nor the socially conscious cheese of late Springsteen. The alienation here is more Freud than Marx: “Don’t look at my face! DON’T LOOK AT MY FACE,” Bruce howls, on “Streets of Fire,” so incapable of solidarity that even eye contact feels intrusive. He introduces a factory only to tell us about a gruesome accident on the floor. This is why the record works, where his later attempts don’t; he doesn’t condescend to his characters. Poverty is just another way to establish the sense they all have of being trapped and desperate; the Working Man is just as depressed as anyone else.

The men of Darkness are invariably Byronic, outcasts, on fire with emotion intense enough to illuminate the landscape like lightning. They’ve always done something horrible, are chased through song after song by unnameable regrets; they have “sins” to wash off their hands, they need something “forgotten or forgiven,” but whatever it was, they can’t say it aloud. “Everybody’s got a secret, son,” one tells us, “something they just can’t face.” They can only keep driving, in the hope of leaving it behind.

The first draft of the funereal “Racing in the Streets” had “no girl in it,” Bruce says. But there aren’t really any girls on Darkness, outside of the eyeball-melting femme fatal in “Candy’s Room.” There are only references to women. And these women are mostly lingering disappointments or aching losses, out on the periphery. Or, worse, they’re the silent, attentive, infantile “babies” and “little darlings” Bruce is always lecturing, as on “Badlands.” You better get it straight, darling: “Poor man wanna be rich! Rich man wanna be king!” And woman, no matter what her income, wanna sit there and listen to her boyfriend explain class struggle, apparently.

But all this man-to-man struggle has a point. No matter what the men on Darkness are, they are never fathers. “Daddy” shows up twice. Once on “Factory,” where he’s a slightly pathetic servant to “mansions of pain.” And again, on the album’s center piece.

Bruce Springsteen, I discovered after ten years of estrangement from my father, had written the world’s best song about being estranged from your father. “Adam Raised a Cain” is one long, Plath-worthy scream: hatred, contempt, pain, hatred, shot through with a love that is almost romantic. We were prisoners of love, a love in chains. He was standing in the door, I was standing in the rain, with the same hot blood burning in our veins. How is that not a scene from The Notebook? But these men can only ever hurt each other: Daddy worked his whole life for nothing but the pain. Now he walks these empty rooms looking for something to blame. And his son reflects the blame back onto him, intensified and sharper.

Cain isn’t a girl, but the listener can be. It was here, on this song, that I stopped listening to Bruce as if he were my father’s voice, and started hearing my own.

When your heart goes dead, it’s always for a reason; something hurts too much to feel. It happens a lot to addicts. No-one can watch that story play out to the end.

Which Bruce knew. It’s the truth he named his album after. It closes, Darkness, on the title track. A man alone, underneath the bridge, on the hill, “’cause I can’t stop,” he says. And for the privilege of not stopping, he’ll pay any price: “I lost my money, and I lost my wife. Them things don’t seem to matter much to me now.” But the girl he’s lost is still out there, somewhere. She could even come to find him. “If she wants to see me,” Bruce yells, and I cry, every time, “you can tell her that I’m easily found.” He even gives the location. “Tell her: There’s a darkness on the edge of town.” But that’s the thing. She already knows. She’s always known. It’s why she’s not there.