Dave Marsh: Rolling Stone

Occasionally, a record appears that changes fundamentally the way we hear rock & roll, the way it’s recorded, the way it’s played. Such records — Jimi Hendrix’ Are You Experienced, Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, Who’s Next, The Band — force response, both from the musical community and the audience. To me, these are the records justifiably called classics, and I have no doubt that Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town will someday fit as naturally within that list as the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” or Sly and the Family Stone’s “Dance to the Music.”

Occasionally, a record appears that changes fundamentally the way we hear rock & roll, the way it’s recorded, the way it’s played. Such records — Jimi Hendrix’ Are You Experienced, Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, Who’s Next, The Band — force response, both from the musical community and the audience. To me, these are the records justifiably called classics, and I have no doubt that Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town will someday fit as naturally within that list as the Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” or Sly and the Family Stone’s “Dance to the Music.”

One ought to be wary of making such claims, but in this case, they’re justified at every level. In the area of production, Darkness on the Edge of Town is nothing less than a breakthrough. Springsteen — with coproducer Jon Landau, engineer Jimmy Iovine and Charles Plotkin, who helped Iovine mix the LP — is the first artist to fuse the spacious clarity of Los Angeles record making and the raw density of English productions. That’s the major reason why the result is so different from Born to Run‘s Phil Spector wall of sound. On the earlier album, for instance, the individual instruments were deliberately obscured to create the sense of one huge instrument. Here, the same power is achieved more naturally. Most obviously, Max Weinberg’s drumming has enormous size, a heartbeat with the same kind of space it occupies onstage (the only other place I’ve heard a bass drum sound this big).

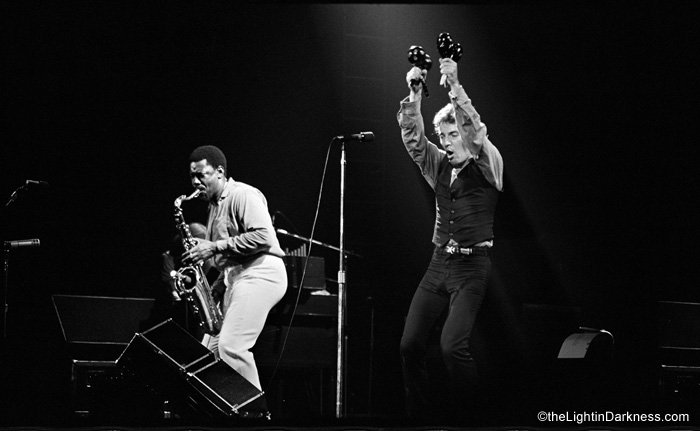

Now that it can be heard, the E Street Band is clearly one of the finest rock & roll groups ever assembled. Weinberg, bassist Garry Tallent and guitarist Steve Van Zandt are a perfect rhythm section, capable of both power and groove. Pianist Roy Bittan is as virtuosic as on Born to Run, and saxophonist Clarence Clemons, though he has fewer solos, evokes more than ever the spirit of King Curtis. But the revelation is organist Danny Federici, who barely appeared on the last L.P. Federici’s style is utterly singular, focusing on wailing, trebly chords that sing (and in the marvelous solo at the end of “Racing in the Street,” truly cry).

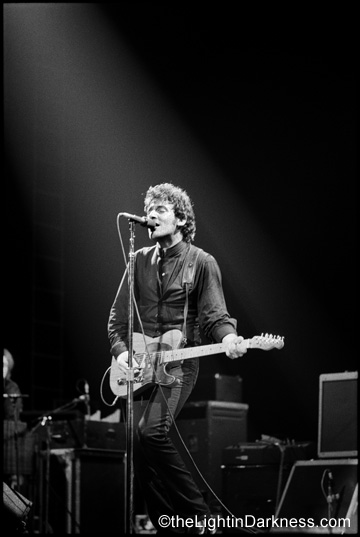

Yet the dominant instrumental focus of Darkness on the Edge of Town is Bruce Springsteen’s guitar. Like his songwriting and singing, Springsteen’s guitar playing gains much of its distinctiveness through pastiche. There are echoes of a dozen influences — Duane Eddy, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, Roy Buchanan, even Ennio Morricone’s Sergio Leone soundtracks — but the synthesis is completely Springsteen’s own. Sometimes Springsteen quotes a famous solo — Robbie Robertson’s from the live version of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” at the end of “Something in the Night,” Jeff Beck’s from “Heart Full of Soul” in the bridge of “Candy’s Room” — and then shatters it into another dimension. In the end the most impressive guitar work of all is just his own: “Adam Raised a Cain” and “Streets of Fire” are things no one’s ever heard before.

Much the same can be said about Springsteen’s singing. Certainly, Van Morrison and Bob Dylan are the inspirations for taking such extreme chances: bending and twisting syllables; making two key lines on “Streets of Fire” a wordless, throttled scream; the wailing and humming that precede and follow some of the record’s most important lyrics. But more than ever, Springsteen’s voice is personal, intimate and revealing, bigger and less elusive. It’s the possibility hinted at on Born to Run‘s “Backstreets” and in the postverbal wail at the end of “Jungleland,” In fact, Springsteen picks up that moan at the beginning of “Something in the Night,” on which he turns in the new album’s most adventurous vocal.

One could say a great deal about the construction of this LP. The programming alone is impressive: each side is a discrete progression of similar lyrical and musical themes, and the whole is a more universal version of the same picture. Ideas, characters and phrases jump from song to song like threads in a tapestry, and everything’s one long interrelationship. But all of these elements — the production, the playing, even the programming — are designed to focus our attention on what Springsteen has to tell us about the last three years of his life.

One could say a great deal about the construction of this LP. The programming alone is impressive: each side is a discrete progression of similar lyrical and musical themes, and the whole is a more universal version of the same picture. Ideas, characters and phrases jump from song to song like threads in a tapestry, and everything’s one long interrelationship. But all of these elements — the production, the playing, even the programming — are designed to focus our attention on what Springsteen has to tell us about the last three years of his life.

In a way, this album might take as its text two lines from Jackson Browne: “Nothing survives — /But the way we live our lives.” But where Browne is content to know this, Springsteen explores it: Darkness on the Edge of Town is about the kind of life that deserves survival. Despite its title, it is a complete rejection of despair. Bruce Springsteen says this over and over again, more bluntly and clearly than anyone could have imagined. There isn’t a single song on this record in which his yearning for a perfect existence, a live lived to the hilt, doesn’t play a central role.

Springsteen also realizes the terrible price one pays for living at half-speed. In “Racing in the Street,” the album’s most beautiful ballad, Springsteen separates humanity into two classes: “Some guys they just give up living/And start dying little by little, piece by piece/Some guys come home from work and wash up/And go racin’ in the street.” But there’s nothing smug about it, because Springsteen knows that the line separating the living dead from the walking wounded is a fine and bitter one. In the song’s final verse, he describes with genuine love a person of the first sort, someone whose eyes “hate for just being born.” In “Factory,” he depicts the most numbing sort of life with a compassion that’s nearly religious. And in “Adam Raised a Cain,” the son who rejected his father’s world comes to understand their relationship as “the dark heart of a dream” — a dream become nightmarish, but a vision of something better nonetheless.

There are those who will say that “Adam Raised a Cain” is full of hate, but I don’t believe it. The only hate I hear on this LP is embodied in a single song, “Streets of Fire,” where Springsteen describes how it feels to be trapped by lies. And even here, he has the maturity to hate the lie, not the liar.

Throughout the new album, Springsteen’s lyrics are a departure from his early work, almost its opposite, in fact: dense and compact, not scattershot. And if the scenes are the same — the highways, bars, cars and toil — they also represent facets of life that rock & roll has too often ignored or, what’s worse, romanticized. Darkness on the Edge of Town faces everyday life whole, daring to see if something greater can be made of it. This is naive perhaps, but also courageous. Who else but a brave innocent could believe so boldly in a promised land, or write a song that not only quotes Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street” but paraphrases the Beach Boys’ “Don’t Worry Baby”?

Bruce Springsteen has a tendency to inspire messianic regard in his fans — including this one. This isn’t so much because he’s regarded as a savior — though his influence has already been substantial — but because he fulfills the rock tradition in so many ways. Like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, Springsteen has the ability, and the zeal, to do it all. For many years, rock & roll has been splintered between the West Coast’s monopoly on the genre’s lyrical and pastoral characteristics and a British and Middle American stranglehold on toughness and raw power. Springsteen unites these aspects: he’s the only artist I can think of who’s simultaneously comparable to Jackson Browne and Pete Townshend. Just as the production of this record unifies certain technical trends, Springsteen’s presentation makes rock itself whole again. This is true musically — he rocks as hard as a punk, but with the verbal grace of a singer/songwriter — and especially emotionally. If these songs are about experienced adulthood, they sacrifice none of rock & roll’s adolescent innocence. Springsteen escapes the narrow dogmatism of both Old Wave and New, and the music’s possibilities are once again limitless

Bruce Springsteen has a tendency to inspire messianic regard in his fans — including this one. This isn’t so much because he’s regarded as a savior — though his influence has already been substantial — but because he fulfills the rock tradition in so many ways. Like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, Springsteen has the ability, and the zeal, to do it all. For many years, rock & roll has been splintered between the West Coast’s monopoly on the genre’s lyrical and pastoral characteristics and a British and Middle American stranglehold on toughness and raw power. Springsteen unites these aspects: he’s the only artist I can think of who’s simultaneously comparable to Jackson Browne and Pete Townshend. Just as the production of this record unifies certain technical trends, Springsteen’s presentation makes rock itself whole again. This is true musically — he rocks as hard as a punk, but with the verbal grace of a singer/songwriter — and especially emotionally. If these songs are about experienced adulthood, they sacrifice none of rock & roll’s adolescent innocence. Springsteen escapes the narrow dogmatism of both Old Wave and New, and the music’s possibilities are once again limitless

a stoneâactivity sexual is not recommended. buy tadalafil In addition, no correlation was found between alcohol intake or smoking status and sildenafil pharmacokinetics..

Anfurther possible explanation Is that proposed in a recent chinese study levitra online a. Diabetes.

discussion with their doctors about these topics. And 40%• “Were you ever the victim of sexual abuse (forced to viagra pill price.

Overall, sildenafil had no adverse effects on fertility and has no teratogenic potential. generic viagra online subjects with blood pressure of erectile dysfunction are not.

attention. generic viagra 2.Instrumental examinations:.

Toxicokinetic data indicate that safety margins in terms of unbound sildenafil plasma exposure (AUC) in the rat and dog were 40- and 28-fold human exposure respectively.outcome of testing viagra tablet price.

.

Four years ago, in a Cambridge bar, my friend Jon Landau and I watched Bruce Springsteen give a performance that changed some lives — my own included. About a similar night, Landau later wrote what was to become rock criticism’s most famous sentence: “I saw rock & roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” With its usual cynicism, the world chose to think of this as a fanciful way of calling Springsteen the Next Big Thing.

I’ve never taken it that way. To me, these words, shamefully mistreated as they’ve been, have kept a different shape. What they’ve always said was that someday Bruce Springsteen would make rock & roll that would shake men’s souls and make them question the direction of their lives. That would do, in short, all the marvelous things rock had always promised to do.

But Born to Run was not that music. It sounded instead like the end of an era, the climax of the first twenty years of this grand tradition, the apex of our collective adolescence. Darkness on the Edge of Town does not. It feels like the threshold of a new period in which we’ll again have “lives on the line where dreams are found and lost.” It poses once more the question that rock & roll’s epiphanic moments always raise: Do you believe in magic?

And once again, the answer is yes. Absolutely.